The Great Historical Atlas

of Czech Silesia

Identity, Culture and Society of Czech Silesia

in the Process of Social Modernisation with an Impact on the Cultural Landscape

Lubor Hruška, Lenka Jarošová, Radek Lipovski (eds.)

ACCENDO - Centre for Science and Research, z. ú.

Ostrava

2021

This publication is published within the project THE GREAT HISTORICAL ATLAS OF CZECH Silesia - Identity, Culture and Society of Czech Silesia in the Process of Social Modernisation with an Impact on the Cultural Landscape; project identification code: DG18P02OVV047; the project is funded by the Programme for the Support of Applied Research and Experimental Development of National and Cultural Identity for the Years 2016 to 2022 (NAKI II).

The subject of the project is a comprehensive mapping of the historical processes that have influenced the population and the landscape, especially after 1848 to the present day, in the territory of Czech Silesia and the territorially related "Moravian Wedge." It is a synthesizing multidisciplinary project that links history, demography, sociology, economics, urban planning and natural sciences. The project integrates the knowledge gained from the previous research projects of three institutions focusing on the territory of Czech Silesia and complements it with other necessary research. This synthesis will provide a new perspective on the development of the territory, which has been subjected to major historical changes within the Central European area, including the interaction between society and the landscape, landscape management (history of forestry, agriculture) and other processes in the territory (impact of mining, war on the landscape). The multidisciplinary research team has the potential to identify completely new causalities between historical processes and the current state of society and landscape (more information on the project website: http://atlas-slezska.cz/).

Leading researcher: ACCENDO - Centre for Science and Research, z. ú.

Co-researcher: Silesian Museum

Co-researcher: Faculty of Arts, University of Ostrava

In cooperation with: Museum of Těšín Region, contributory organization

Keywords: Silesia, history, landscape, culture, identity, atlas

Editors: Lubor Hruška – Lenka Jarošová – Radek Lipovski

Reviewers:

prof. PhDr. Zdeněk Jirásek, CSc. – Silesian University in Opava, Department of Historical Sciences

doc. Ing. Petr Jančík, Ph.D. – VŠB - Technical University Ostrava, Institute of Environmental Technologies

Author’s collective:

Jiří Brňovják, Lukáš Číhal, Lumír Dokoupil, Ivana Foldynová, Martin Gajdošík, Dan Gawrecki, Tomáš Herman, Jana Horáková, Lubor Hruška, Andrea Hrušková, Lenka Jarošová, Radim Jež, Pavel Kladiwa, Ondřej Kolář, Ivana Kolářová, Igor Kyselka, Radek Lipovski, Ludmila Nesládková, Zbyšek Ondřeka, Karolína Ondřeková, David Pindur, Andrea Pokludová, Petr Popelka, Renata Popelková, Dagmar Saktorová, Pavel Šopák, Marta Šopáková, Oľga Šrajerová, Aleš Zářický, Michaela Závodná

Cartographic outputs:

Igor Ivan, David Kubáň, Peter Golej, Ondřej Kolodziej

The subject of the project is a comprehensive mapping of the historical processes that have influenced the population and the landscape, especially after 1848 to the present day, in the territory of Czech Silesia and the territorially related "Moravian Wedge." It is a synthesizing multidisciplinary project that links history, demography, sociology, economics, urban planning and natural sciences. The project integrates the knowledge gained from the previous research projects of three institutions focusing on the territory of Czech Silesia and complements it with other necessary research. This synthesis will provide a new perspective on the development of the territory, which has been subjected to major historical changes within the Central European area, including the interaction between society and the landscape, landscape management (history of forestry, agriculture) and other processes in the territory (impact of mining, war on the landscape). The multidisciplinary research team has the potential to identify completely new causalities between historical processes and the current state of society and landscape (more information on the project website: http://atlas-slezska.cz/).

Leading researcher: ACCENDO - Centre for Science and Research, z. ú.

Co-researcher: Silesian Museum

Co-researcher: Faculty of Arts, University of Ostrava

In cooperation with: Museum of Těšín Region, contributory organization

Keywords: Silesia, history, landscape, culture, identity, atlas

Editors: Lubor Hruška – Lenka Jarošová – Radek Lipovski

Reviewers:

prof. PhDr. Zdeněk Jirásek, CSc. – Silesian University in Opava, Department of Historical Sciences

doc. Ing. Petr Jančík, Ph.D. – VŠB - Technical University Ostrava, Institute of Environmental Technologies

Author’s collective:

Jiří Brňovják, Lukáš Číhal, Lumír Dokoupil, Ivana Foldynová, Martin Gajdošík, Dan Gawrecki, Tomáš Herman, Jana Horáková, Lubor Hruška, Andrea Hrušková, Lenka Jarošová, Radim Jež, Pavel Kladiwa, Ondřej Kolář, Ivana Kolářová, Igor Kyselka, Radek Lipovski, Ludmila Nesládková, Zbyšek Ondřeka, Karolína Ondřeková, David Pindur, Andrea Pokludová, Petr Popelka, Renata Popelková, Dagmar Saktorová, Pavel Šopák, Marta Šopáková, Oľga Šrajerová, Aleš Zářický, Michaela Závodná

Cartographic outputs:

Igor Ivan, David Kubáň, Peter Golej, Ondřej Kolodziej

An interactive version of the atlas in four languages (Czech, Polish, English and German) can be found at: http://mapa.atlas-slezska.cz

In addition to publicly available web sources, the authors of ATLAS also used private sources. The authors of ATLAS would like to thank the following institutions and persons for their permission to use their funds, collections and photographs to create the pictorial parts of ATLAS. Photographs and maps © City of Ostrava Archives - Statutory City of Ostrava; Archives of the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, Prague; Czech Geodetic and Cartographic Office, Prague; Czechoslovak Hussite Church; Muzeum Śląska Cieszyńskiego; Museum of Těšín; National Museum, Prague; Religious Community of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church, Ostrava-Radvanice; National Heritage Institute; Niederösterreichisches Landesarchiv St. Pölten; Municipal Office Sedliště; Silesian Museum; Central Archives of Surveying and Cartography, Prague; Zemský archiv v Opavě; Zemský archiv v Opavě, State District Archive Bruntál with seat in Krnov; Zemský archiv v Opavě, State District Archive Frýdek-Místek; Zemský archiv v Opavě, Státní okresní archiv Jeseník; Zemský archiv v Opavě, Státní okresní archiv Karviná; Zemský archiv v Opavě, Státní okresní archiv Nový Jičín; Vagon Museum in Studénka, Military Geographical and Hydrometeorological Office Dobruška and M. Anděra; D. Baránek; O. Boháč; J. Bohdal; J. Brňovják; L. Číhal; J. Hamza; J. Horáková; V. Hrazdil; M. Hykel; T. Indruch; R. Janda; L. Jarošová; Z. Jordanidu; J. Juchelka; S. Juga; J. Jung; Z. Kittrich; O. Klusák; J. Kristiánová; J. Křesina; P. Koudelka; O. Kolář; I. Kozelek; J. Kubica; P. Lazárková; I. Lička; B. Lojkásek; J. Mach; K. Müller; F. Nesvadba; M. Pešata; M. Pietoň; D. Pindur; Z. Pohoda; A. Pokludová; M. Polák; M. Polášek; A. Pončová; A. Prágr; P. Proske; A. Pustka; L. Pustka; Š. Rak; V. Reichman; J. Roháček; P. Rödl; D. Saktorová; J. Sejkora; E. Schweserová; F. Sokol; J. Solnický; P. Suvorov; K. Šimeček; M. Šišmiš; P. Šopák; M. Šos; V. Švorčík; T. Urbánková; J. Vaněk; L. Wünsch; J. Zajíc; I. Zwach.

The aerial photographs (I. Kozelek - T. Indruch) were taken within the project "The Czech-Polish Border Region from a Bird’s Eye View." The project was implemented in 2011 by the town of Krnov in cooperation with the partner town of Hlubčice with the financial support of the European Regional Development Fund.

In addition to publicly available web sources, the authors of ATLAS also used private sources. The authors of ATLAS would like to thank the following institutions and persons for their permission to use their funds, collections and photographs to create the pictorial parts of ATLAS. Photographs and maps © City of Ostrava Archives - Statutory City of Ostrava; Archives of the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, Prague; Czech Geodetic and Cartographic Office, Prague; Czechoslovak Hussite Church; Muzeum Śląska Cieszyńskiego; Museum of Těšín; National Museum, Prague; Religious Community of the Czechoslovak Hussite Church, Ostrava-Radvanice; National Heritage Institute; Niederösterreichisches Landesarchiv St. Pölten; Municipal Office Sedliště; Silesian Museum; Central Archives of Surveying and Cartography, Prague; Zemský archiv v Opavě; Zemský archiv v Opavě, State District Archive Bruntál with seat in Krnov; Zemský archiv v Opavě, State District Archive Frýdek-Místek; Zemský archiv v Opavě, Státní okresní archiv Jeseník; Zemský archiv v Opavě, Státní okresní archiv Karviná; Zemský archiv v Opavě, Státní okresní archiv Nový Jičín; Vagon Museum in Studénka, Military Geographical and Hydrometeorological Office Dobruška and M. Anděra; D. Baránek; O. Boháč; J. Bohdal; J. Brňovják; L. Číhal; J. Hamza; J. Horáková; V. Hrazdil; M. Hykel; T. Indruch; R. Janda; L. Jarošová; Z. Jordanidu; J. Juchelka; S. Juga; J. Jung; Z. Kittrich; O. Klusák; J. Kristiánová; J. Křesina; P. Koudelka; O. Kolář; I. Kozelek; J. Kubica; P. Lazárková; I. Lička; B. Lojkásek; J. Mach; K. Müller; F. Nesvadba; M. Pešata; M. Pietoň; D. Pindur; Z. Pohoda; A. Pokludová; M. Polák; M. Polášek; A. Pončová; A. Prágr; P. Proske; A. Pustka; L. Pustka; Š. Rak; V. Reichman; J. Roháček; P. Rödl; D. Saktorová; J. Sejkora; E. Schweserová; F. Sokol; J. Solnický; P. Suvorov; K. Šimeček; M. Šišmiš; P. Šopák; M. Šos; V. Švorčík; T. Urbánková; J. Vaněk; L. Wünsch; J. Zajíc; I. Zwach.

The aerial photographs (I. Kozelek - T. Indruch) were taken within the project "The Czech-Polish Border Region from a Bird’s Eye View." The project was implemented in 2011 by the town of Krnov in cooperation with the partner town of Hlubčice with the financial support of the European Regional Development Fund.

© ACCENDO - Centre for Science and Research, z. ú., 2021

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of abbreviations

| a. v. | Augsburg confession |

| AMO | Archive of the city of Ostrava - Statutory City of Ostrava |

| AOPK | Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic |

| c. k. | Imperial-Royal |

| ČCE | Czech Evangelical Church |

| CČS | Church of Czechoslovakia |

| CČSH | Czechoslovak Hussite Church |

| ČR | Czech Republic |

| ČSAD | Czechoslovak Automobile Transport |

| ČSD | Czechoslovak Railways |

| ČSR | Czechoslovak Republic |

| ČSSS | Czechoslovak State Farms |

| ČSTV | Czechoslovak Union of Physical Education and Sport |

| ČSÚ | Czech Statistical Office |

| ČÚZK | Czech Office of Surveying and Cartography |

| DMR | Digital elevation model |

| CHKO | Protected landscape area |

| JZD | Unified agricultural cooperative |

| k. ú. | Cadastral territory |

| KSČ | Communist Party of Czechoslovakia |

| KBD | Košice-Bohumín railway |

| LECAV | Lutheran Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in the Czech Republic |

| LFA | Less favour areas |

| MHD | Public transport |

| MLL | Masaryk aviation league |

| MT | Museum of Těšín Region |

| MSK | Moravian-Silesian Region |

| MŚC | Muzeum of Cieszyn Silesia |

| MU | Masaryk University |

| MV ČR | Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic |

| MZV ČR | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic |

| n. p. | National enterprise |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NHKG | New Steelworks of Klement Gottwald |

| NM | National Museum |

| NPR | National Nature Reserve |

| NPÚ | National Heritage Institute |

| OKD | Ostrava-Karviná Mines |

| OKR | Ostrava-Karviná Mining District |

| OLK | Olomouc Region |

| OU | University of Ostrava |

| OÚ | Municipal Authority |

| ÖNB | Österreichische Nationalbibiothek Wien |

| PR | Nature Reserve |

| PřF | Faculty of Natural Sciences |

| RVHP | The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance |

| s. o. | Judicial district |

| s. p. | State enterprise |

| s. r. o. | Private limited company |

| SCEAV | Silesian Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession |

| SLDB | Census of Population, Houses and Flats |

| SO OPR | Administrative district of a municipality with extended competence |

| SOkA Bruntál | Provincial Archives in Opava, State District Archives in Bruntál with seat in Krnov |

| SOkA Frýdek-Místek | Provincial Archives in Opava , State District Archives in Frýdek-Místek |

| SOkA Jeseník | Provincial Archives in Opava, State District Archives in Jeseník |

| SOkA Karviná | Provincial Archives in Opava, State District Archives in Karviná |

| SOkA Nový Jičín | Provincial Archives in Opava, State District Archives in Nový Jičín |

| StS | State Farm |

| SZM | Silesian Provincial Museum |

| SZEŠ | Secondary Agricultural School |

| SZTŠ | Secondary Agricultural Technical School |

| ÚAZK | Central Archive of Surveying and Cadastre |

| VGHMÚř | Military Geographical and Hydrometeorological Office Dobruška |

| VOKD | Construction - Ostrava-Karviná Mines |

| z. ú. | registered institute |

| ZAO | Provincial Archives in Opava |

| zl | Polish zloty (currency) |

| ZPF | Agricultural land fund |

| ŽNO | Jewish religious community |

Subregions of Czech Silesia

Justification of the written form of the connection between Czech, Austrian, Prussian and Těšín Silesia

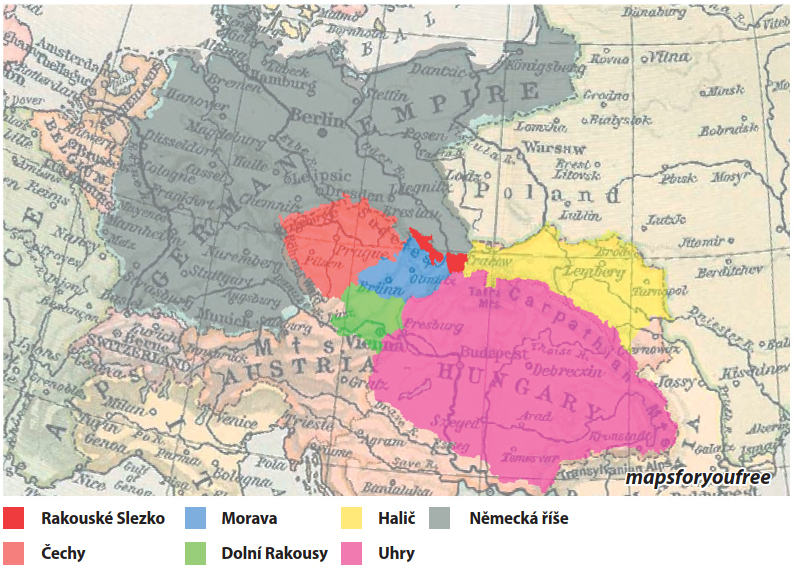

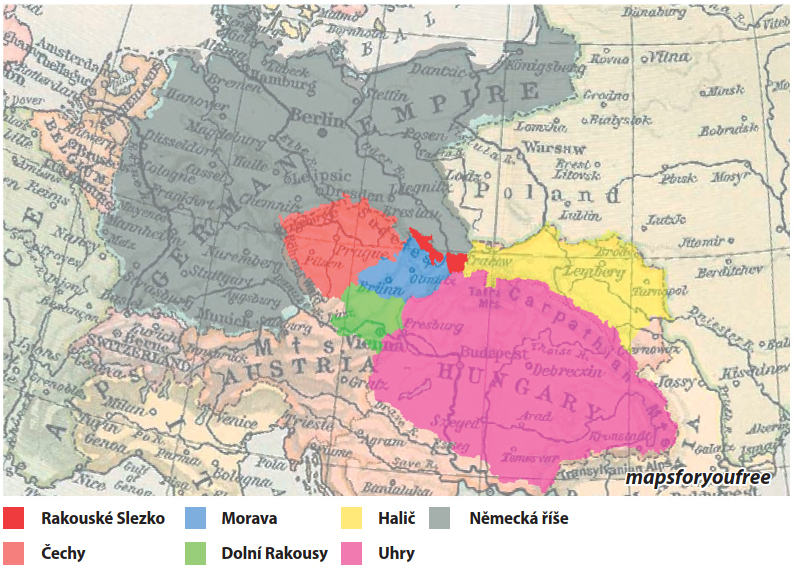

Nowadays, we encounter diverse variants of the written form of the name “CZECH SILESIA.” On the one hand, the arguments are based on conformity with the current form of linguistic codification, on the other hand, they seek support in the customary use of similar names (e.g. Austrian Silesia) in writing. The collective of authors decided to keep in line with the currently valid grammar of the Czech language, and therefore we use the name Czech Silesia in the text. In the following, we briefly present the arguments for this decision. It is a two-word name composed of an adjective and a proper noun, where the proper noun is not part of the geographical name and only indicates the closer localization of the territory denoted by the proper noun (similar example Opava Silesia = the territory in Silesia around the town of Opava). At the same time, in the case of the written form of the designation Czech Silesia the rule for combining an adjective and the name of a region, micro-region or Euroregion cannot be applied, as in the case of Těšín Silesia, which has been a Euroregion since 1998 thanks to the launch of a Euro-programme supporting cross-border cooperation in this area. In the end, we cannot rely on the rule of writing historical names of states as in the case of Austrian Silesia, which became one of the crown lands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with its capital Opava by imperial decision in the period of 1850-1918 (note that we can also balance linguistically here, as the official name of this duchy was Upper and Lower Silesia).

Following the above arguments and taking into account the primary goal of the authors to comprehensively map the historical processes that have influenced the population and the landscape, especially after 1848 until the present day in the territory of Czech Silesia and the territorially related “Moravian Wedge,” the author’s team decided to apply the written form of Austrian, Prussian and Těšín Silesia in the same way. For the first two, we rely on the argument of the absence of an official historical name; for Těšín Silesia, we work with a different temporal and spatial definition than the current Euroregion.

Nowadays, we encounter diverse variants of the written form of the name “CZECH SILESIA.” On the one hand, the arguments are based on conformity with the current form of linguistic codification, on the other hand, they seek support in the customary use of similar names (e.g. Austrian Silesia) in writing. The collective of authors decided to keep in line with the currently valid grammar of the Czech language, and therefore we use the name Czech Silesia in the text. In the following, we briefly present the arguments for this decision. It is a two-word name composed of an adjective and a proper noun, where the proper noun is not part of the geographical name and only indicates the closer localization of the territory denoted by the proper noun (similar example Opava Silesia = the territory in Silesia around the town of Opava). At the same time, in the case of the written form of the designation Czech Silesia the rule for combining an adjective and the name of a region, micro-region or Euroregion cannot be applied, as in the case of Těšín Silesia, which has been a Euroregion since 1998 thanks to the launch of a Euro-programme supporting cross-border cooperation in this area. In the end, we cannot rely on the rule of writing historical names of states as in the case of Austrian Silesia, which became one of the crown lands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with its capital Opava by imperial decision in the period of 1850-1918 (note that we can also balance linguistically here, as the official name of this duchy was Upper and Lower Silesia).

Following the above arguments and taking into account the primary goal of the authors to comprehensively map the historical processes that have influenced the population and the landscape, especially after 1848 until the present day in the territory of Czech Silesia and the territorially related “Moravian Wedge,” the author’s team decided to apply the written form of Austrian, Prussian and Těšín Silesia in the same way. For the first two, we rely on the argument of the absence of an official historical name; for Těšín Silesia, we work with a different temporal and spatial definition than the current Euroregion.

HOME

The territory of Czech Silesia today forms a very diverse region, which is composed of several regions: the Opava, Hlučín, Ostrava, Těšín and Jesenice regions. The vast majority of the area lies in the Moravian-Silesian Region, with the western end (Jesenicko) in the Olomouc Region. In the current administrative structure of the Czech Republic, its borders are not easily defined, as the borders of Czech Silesia currently cross the territory of several municipalities and towns (e.g. Ostrava, Frýdek-Místek). The imprint of the historical memory of Silesia is still evident here, both in the settlement structure, the landscape and the creative human activity in it, and in the minds of the people living in this area, in their customs, values and culture.

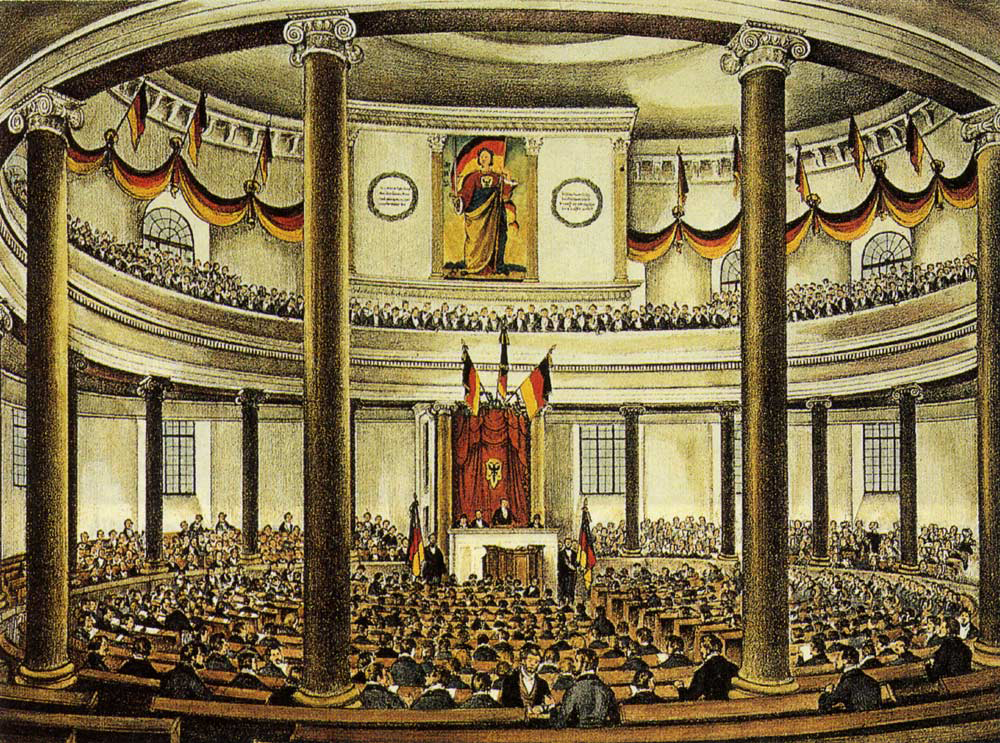

The “Great Historical Atlas of Czech Silesia” (ATLAS) was created by a multidisciplinary team of experts in history, demography, sociology, economics, urban planning and natural sciences. The synthesis of expert knowledge, which is interpreted in a user-friendly way in ATLAS, has created a comprehensive view of the development of a territory that has often been subject to major historical changes within the Central European area. The Silesian Wars is the name given to the three military conflicts between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Habsburg Monarchy, fought between 1740 and 1763 for control of the formerly Austrian region of Silesia. As a result of these conflicts, Silesia was divided into an Austrian and a Prussian part (still alive today and popularly known as the “‘Kaiser”‘ and “‘Prussian”‘). At the time of the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a dispute also arose between the newly-constituted states of Czechoslovakia and Poland over the Těšín Region. Another significant event in the transformation of the territory was the displacement of the inhabitants to Germany after the Second World War, which affected the Jeseníky region in particular. All these events had a major impact on the historical memory of the inhabitants living there, on their perception of their identity with the territory and on socio-cultural development.

ATLAS integrates the knowledge obtained from research projects of several institutions focused on the territory of Czech Silesia. These institutions are ACCENDO - Centre for Science and Research, z. ú., the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ostrava, the Silesian Museum, especially its Silesian Institute. Cooperation with the Museum of Těšínsko was also important for the creation of ATLAS.

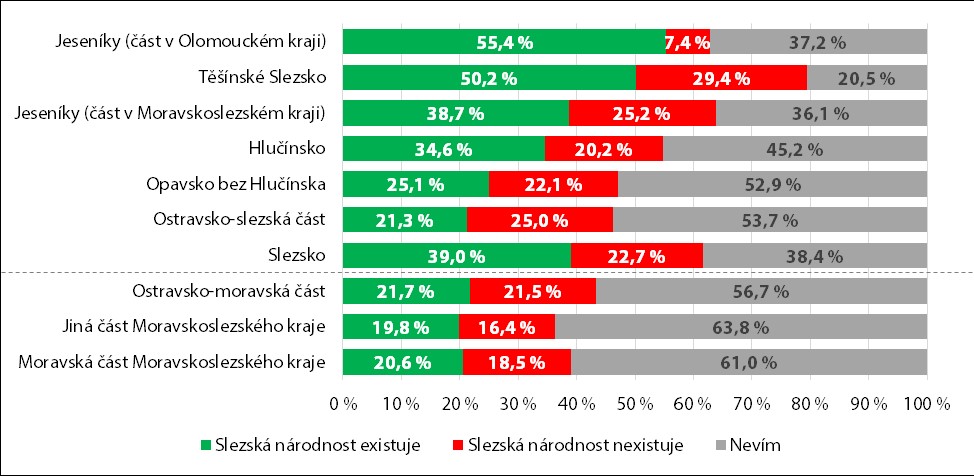

ATLAS consists of a set of annotated maps representing the area of Czech Silesia in seven sections dealing with physical geography, historical geography, demography, socio-cultural development, economic processes, landscape development and the identity of the inhabitants of the area. The multidisciplinary team, thanks to its previous long-term professional experience with work on the above topics, had the potential not only to compare changes, but above all to identify completely new causalities between historical processes and the current state of society and landscape. In addition to historical and geographical information, the team also worked with sociological concepts of identity and culture. The means for obtaining sociological information about the inhabitants of the study area was an extensive quantitative survey of a sample of the population (3000 respondents), which was deepened by a qualitative investigation in the form of 10 group discussions in five areas of the study area. The information obtained is incorporated in the seventh section of the ATLAS.

The “Great Historical Atlas of Czech Silesia” (ATLAS) was created by a multidisciplinary team of experts in history, demography, sociology, economics, urban planning and natural sciences. The synthesis of expert knowledge, which is interpreted in a user-friendly way in ATLAS, has created a comprehensive view of the development of a territory that has often been subject to major historical changes within the Central European area. The Silesian Wars is the name given to the three military conflicts between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Habsburg Monarchy, fought between 1740 and 1763 for control of the formerly Austrian region of Silesia. As a result of these conflicts, Silesia was divided into an Austrian and a Prussian part (still alive today and popularly known as the “‘Kaiser”‘ and “‘Prussian”‘). At the time of the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a dispute also arose between the newly-constituted states of Czechoslovakia and Poland over the Těšín Region. Another significant event in the transformation of the territory was the displacement of the inhabitants to Germany after the Second World War, which affected the Jeseníky region in particular. All these events had a major impact on the historical memory of the inhabitants living there, on their perception of their identity with the territory and on socio-cultural development.

ATLAS integrates the knowledge obtained from research projects of several institutions focused on the territory of Czech Silesia. These institutions are ACCENDO - Centre for Science and Research, z. ú., the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ostrava, the Silesian Museum, especially its Silesian Institute. Cooperation with the Museum of Těšínsko was also important for the creation of ATLAS.

ATLAS consists of a set of annotated maps representing the area of Czech Silesia in seven sections dealing with physical geography, historical geography, demography, socio-cultural development, economic processes, landscape development and the identity of the inhabitants of the area. The multidisciplinary team, thanks to its previous long-term professional experience with work on the above topics, had the potential not only to compare changes, but above all to identify completely new causalities between historical processes and the current state of society and landscape. In addition to historical and geographical information, the team also worked with sociological concepts of identity and culture. The means for obtaining sociological information about the inhabitants of the study area was an extensive quantitative survey of a sample of the population (3000 respondents), which was deepened by a qualitative investigation in the form of 10 group discussions in five areas of the study area. The information obtained is incorporated in the seventh section of the ATLAS.

The main objective of ATLAS is to identify the historical processes that have influenced the population and landscape after 1848 to the present in the territory of Czech Silesia and the territorially related“Moravian Wedge,” the mutual interactions between society and the landscape, landscape management (history of forestry, agriculture) and other processes in the area (influence of mining, war) were described. In general, it is about the development of the society of Czech Silesia in the process of modernisation with an impact on the cultural landscape in which people have lived for centuries. In addition to the main objective, there are sub-objectives that illustrate the whole situation. The causality of the development of territorial, regional, national and cultural identity is mapped and explained, including the development of the inhabitants’’ satisfaction with the quality of life and their perception of the landscape in which they live. The data, which are cartographically mapped onto the territory, explain long-standing economic and socio-demographic processes, including the evolution of the settlement structure. At the same time, by comprehensively mapping the specifics of the development of a cultural landscape that has undergone dramatic changes, traces of events in the landscape are identified to document the changes that have taken place in the territory. The multi-disciplinary approach to ATLAS has allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the landscape, the socio-economic activities within it, and has also, as a result, expanded the possibilities of historical museum presentations to include perspectives from the various natural and social science disciplines that explain the interrelated historical and contemporary influences of populations on the landscape and settlements.

Since the information presented here has a transnational scope, it can be assumed that it will serve as a basis for the current discussion on the problems of national identity and for tracing the evolution of the relationship between humans and landscapes. The authors believe that the information obtained can be used both for museum presentations and for the education of pupils, students and inhabitants of the area.

Since the information presented here has a transnational scope, it can be assumed that it will serve as a basis for the current discussion on the problems of national identity and for tracing the evolution of the relationship between humans and landscapes. The authors believe that the information obtained can be used both for museum presentations and for the education of pupils, students and inhabitants of the area.

1. HISTORICAL-GEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXT

CONTENTS OF THE CHAPTER

1.1 Origin of settlements

Ing. arch. Dagmar Saktorová (ACC), Ing. Ivana Foldynová, Ph.D. (ACC)

1.2 Types of settlements

Ing. arch. Dagmar Saktorová (ACC)

1.3 Development of the state border between 1742-1918

PhDr. Radim Jež, Ph.D. (OU)

1.4 Development of the state border from 1918

PhDr. Radim Jež, Ph.D. (OU)

1.5 Development of the internal administrative structure 1742-1918

Mgr. Karolína Ondřeková (ACC), Mgr. Radek Lipovski, Ph.D. (OU)

1.6 Development of the internal administrative structure since 1918

Mgr. Karolína Ondřeková (ACC), Mgr. Radek Lipovski, Ph.D. (OU)

1.7 Development of buildings in the territory of Czech Silesia

Ing. arch. Dagmar Saktorová (ACC)

Ing. arch. Dagmar Saktorová (ACC), Ing. Ivana Foldynová, Ph.D. (ACC)

1.2 Types of settlements

Ing. arch. Dagmar Saktorová (ACC)

1.3 Development of the state border between 1742-1918

PhDr. Radim Jež, Ph.D. (OU)

1.4 Development of the state border from 1918

PhDr. Radim Jež, Ph.D. (OU)

1.5 Development of the internal administrative structure 1742-1918

Mgr. Karolína Ondřeková (ACC), Mgr. Radek Lipovski, Ph.D. (OU)

1.6 Development of the internal administrative structure since 1918

Mgr. Karolína Ondřeková (ACC), Mgr. Radek Lipovski, Ph.D. (OU)

1.7 Development of buildings in the territory of Czech Silesia

Ing. arch. Dagmar Saktorová (ACC)

1.1 Origin of settlements

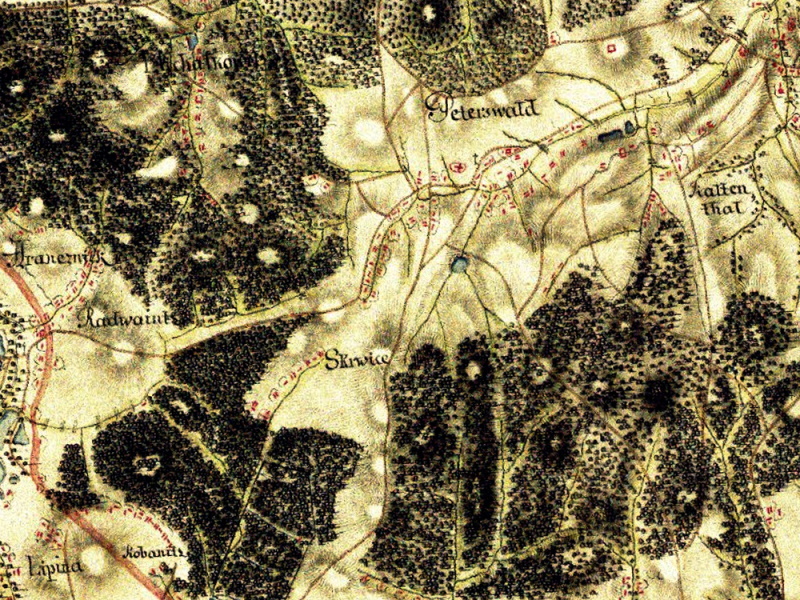

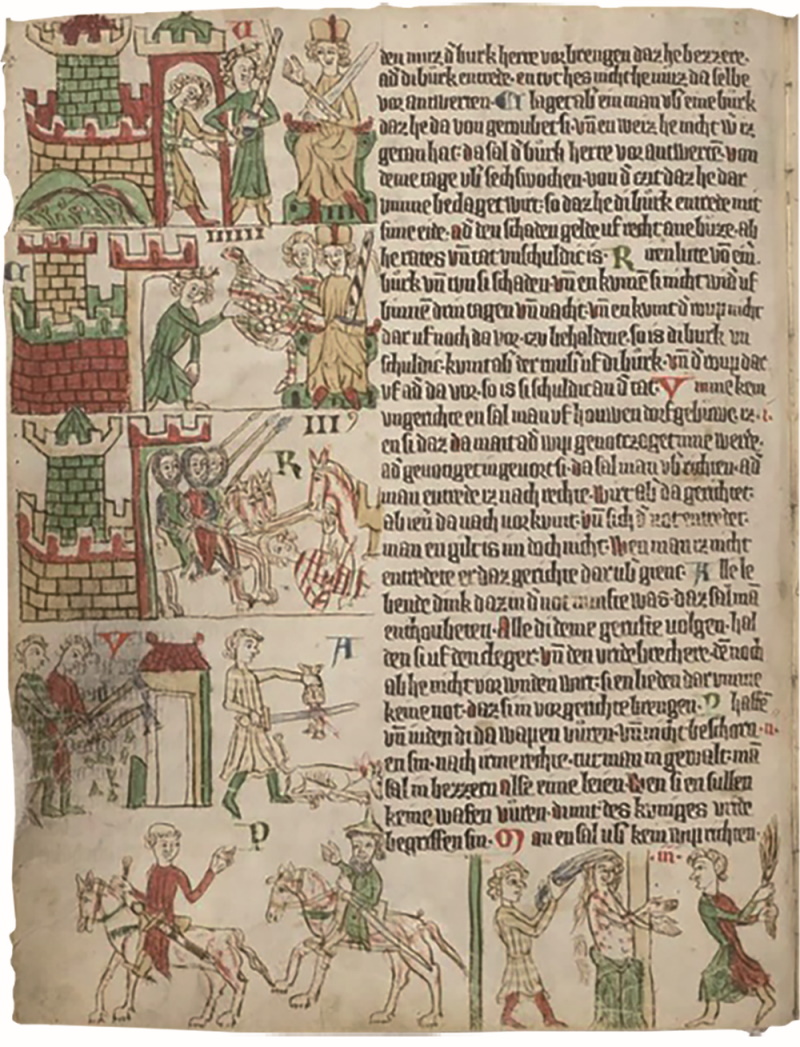

In the process of settling Silesia, the ancient pattern of penetration along streams (rivers, streams, rivulets) was applied. The agricultural population settled first in the lowlands. The routes of trade routes, especially the so-called Amber Route from the Baltic to the Adriatic and the so-called Reed Route connecting Prague with Cracow, had a considerable influence on the location of settlements.

The later formation of the settlement network in most of the territory is linked to medieval colonisation, which brought the founding of new towns and villages, most of which have survived to the present day. From the 12th century onwards, internal colonisation took place, with the indigenous population playing a major role, but the sub-state transformation was linked to external colonisation, which began in the second half of the 13th century, continued in the 14th century, and continued in the mountain areas even later. It was the initiative of the rulers and the high representatives of the Church and the nobility. During this process, the forests were gradually lost through clearing and grubbing up and the agricultural landscape was added to. Colonists came to Silesia from various countries. The German stream prevailed, heading upstream along the Elbe through Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, with its destination in Upper Hungary. The settlers brought new legal norms for both the urban (Swabian and Saxon Mirror) and rural populations (emphyteutic law). The influx of the population led to the settlement of higher ground, where a number of new villages were established, whose populations had to cope with unfavourable natural conditions.

Locators were commissioned by landowners to found new towns on green turf (in uninhabited areas) or on the site of former villages. These towns, unlike the older ones, were "growing" cities characterized by a regular plan. Among the first to be founded were the so-called upper towns, when new settlers were attracted by the great mineral wealth of Silesia (the Golden Mountains). Their patrons were often the bishops of Wrocław and Piast princes. The construction or reconstruction of medieval castles (Hradec nad Moravicí, Hukvaldy, Landek, Vikštejn, etc.) also stimulated the settlement. A new model of agricultural production was formed, which brought about the extension of the three-field system (winter, spring, fallow). The regular arrangement of the arable land led to a transition from extensive to intensive production, and agricultural tools were improved.

A noticeable intervention in the development of the settlement in the 15th century was the Hungarian war campaigns. Many castles were captured and villages were devastated, many of which were not rebuilt. The nobility took advantage of this to seize unsettled land and expand their estates. In addition to the growing interest in mining precious metals (gold, silver), the economic activities of the nobility (e.g. a new focus on iron ore mining and metallurgy) also increased. In the Poodrie region, fish farming developed and new settlements were founded.

From the beginning of the 16th century, a new phenomenon began to take hold, which was the so-called Wallachian colonisation. The Wallachians came to Těšín and Eastern Moravia from the east along the Carpathian Arch. Their specificity was the mountain way of cattle breeding and the production of sheep products. In spring, the flocks were driven to shepherds’’ huts in the mountains, where they were kept in unroofed pens (koshars) until autumn. In the 17th century, the so-called shepherd colonisation also spread upstream of the rivers and streams, and the two groups intermingled and merged. The Thirty Years’’ War brought about a depopulation of the population and the devastation of settlements - towns and villages, especially along the routes of military movements and clashes. However, there were no major changes in the settlement network. The post-war period saw the culmination of the process of strengthening the landlord economy, the differentiation of the nobility, including changes in the composition of the estate (the departure of non-Catholics).

The last intervention into the settlement conditions of the still traditional society was the parcelling of the courts and the Josephine colonization associated with the establishment of new settlements. The reason for this was the fact that the tax revenue from the land parcelled out was higher than the earnings from the owners’’ own farming. On the initiative of the Austrian economist Raab, the so-called Raabisation settlements were founded, characterised by a very regular layout. In the territory of Czech Silesia, these included Ditrichštejn (today part of the town of Jeseník), Lipina (today part of the municipality of Štáblovice), Tábor (today part of the municipality of Velké Heraltice) and others. In the 18th century, the long-term process of settling the landscape was basically completed. A new impetus was provided by the industrialisation that developed from the 19th century onwards, as well as by the massive support for mining and the development of heavy industry in Czechoslovakia after the Second World War.

1.2 Types of settlements

The area of today’s Czech Silesia basically comprises three areas of rural settlement according to the types of settlements and the regularity of their layout and two basic historical types of towns.

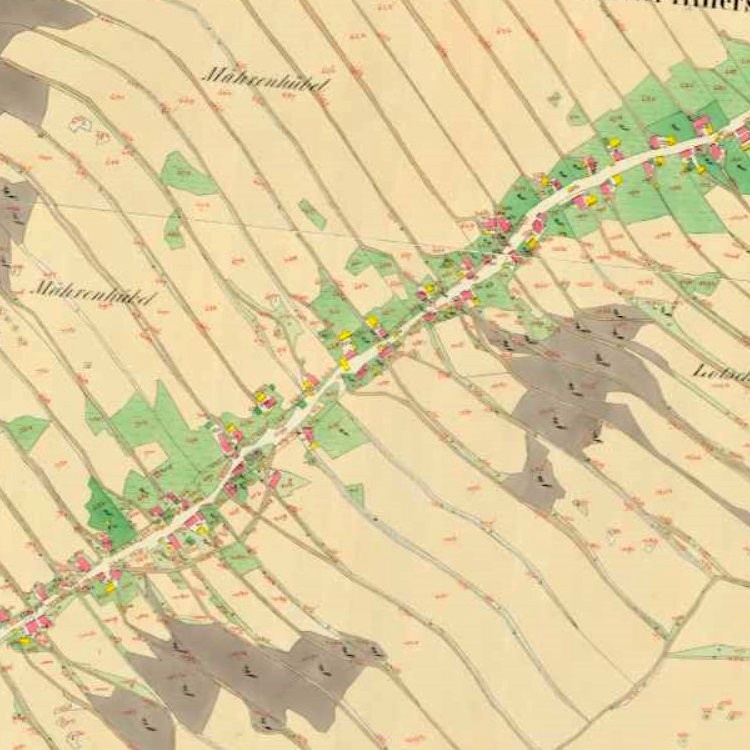

In the middle areas, previously covered by continuous forests and settled during the late medieval colonization, the villages have a more loose but regular layout with a greater distance between the homesteads. The axis of these terraced villages, otherwise known as woodland rope villages, is usually a stream and a road. In contrast to the previous type, the owners’ landholdings are concentrated in a belt behind the homesteads, forming what is known as a “ploughland”. The boundaries of these strips are still visible in many places thanks to the mature trees that line them. The extensive area of the rope villages covers the whole of the Hrubý and Nízký Jeseník with the exception of the highest altitudes and part of the Poodří and Podbeskydí. The best preserved are the rope ploughlands in the Holčovice region.

The chain villages of the Beskydy sub-region and parts of Ostrava have a similar, but even looser and less regular layout, forming a transitional type to the third and least regular type - the dispersed settlement of Těšín Silesia with a pluvial system of divided sections. The mass villages of the higher altitudes of the Beskydy Mountains also have an irregular layout. However, mixed-type villages are also abundant in Czech Silesia.

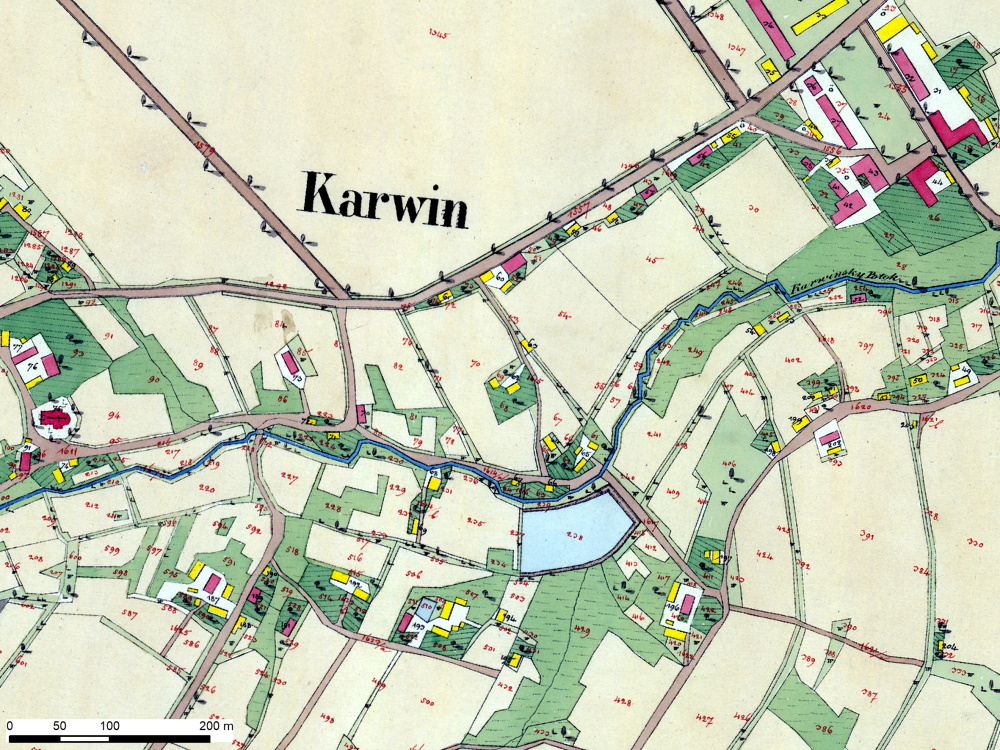

The towns of Czech Silesia, as they aged over the years, bear some characteristics of colonial towns. Regular core area of central square, either square or rectangular plan and a more or less rectangular grid of paths branching out of it. The exceptions are Krnov and Opava (and Těšín on the Polish side), whose irregular layout indicates an older origin. New towns were also founded on the site of earlier villages, which were covered by the new parcelization. It was not until relatively recent times that the town of Havířov was founded (in the 1950s), but also Český Těšín, which was built according to the urban plan as a new town after the division of Těšín by the Czech-Polish border. The extinct settlements include the original rope village of Karviná (now Karviná-Doly), which had to give way to coal mining.

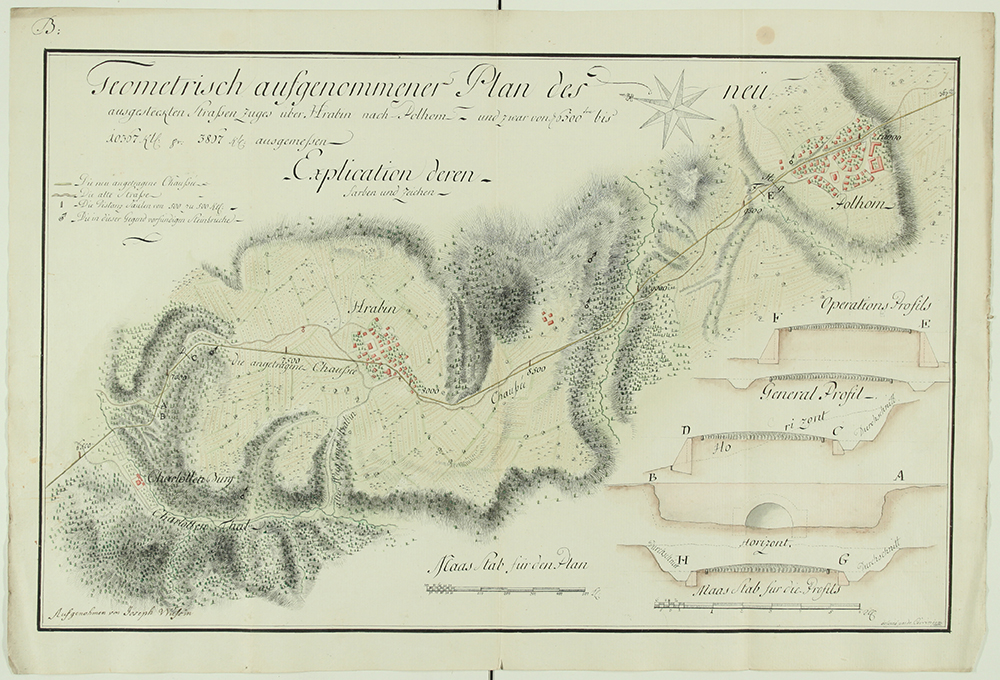

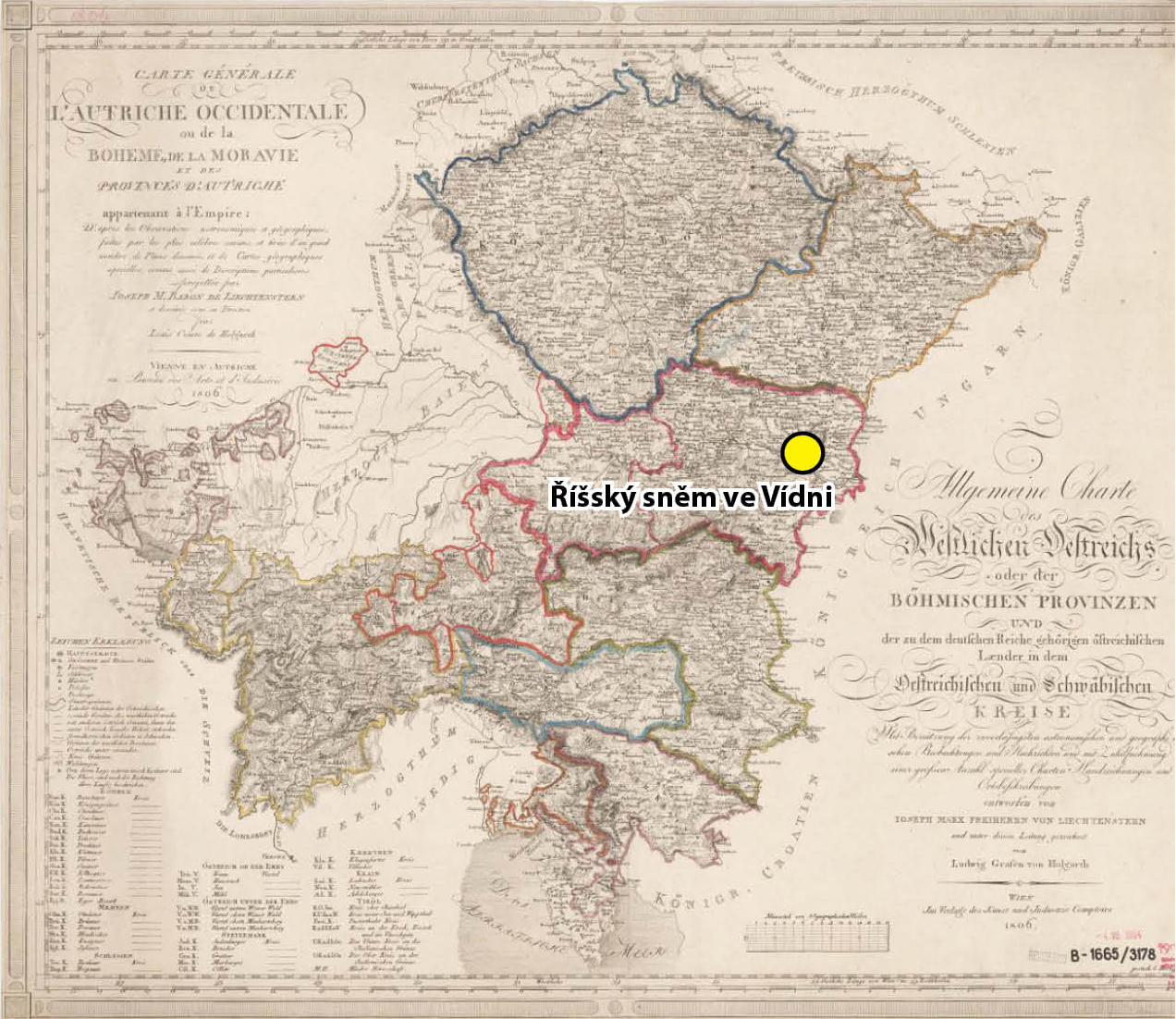

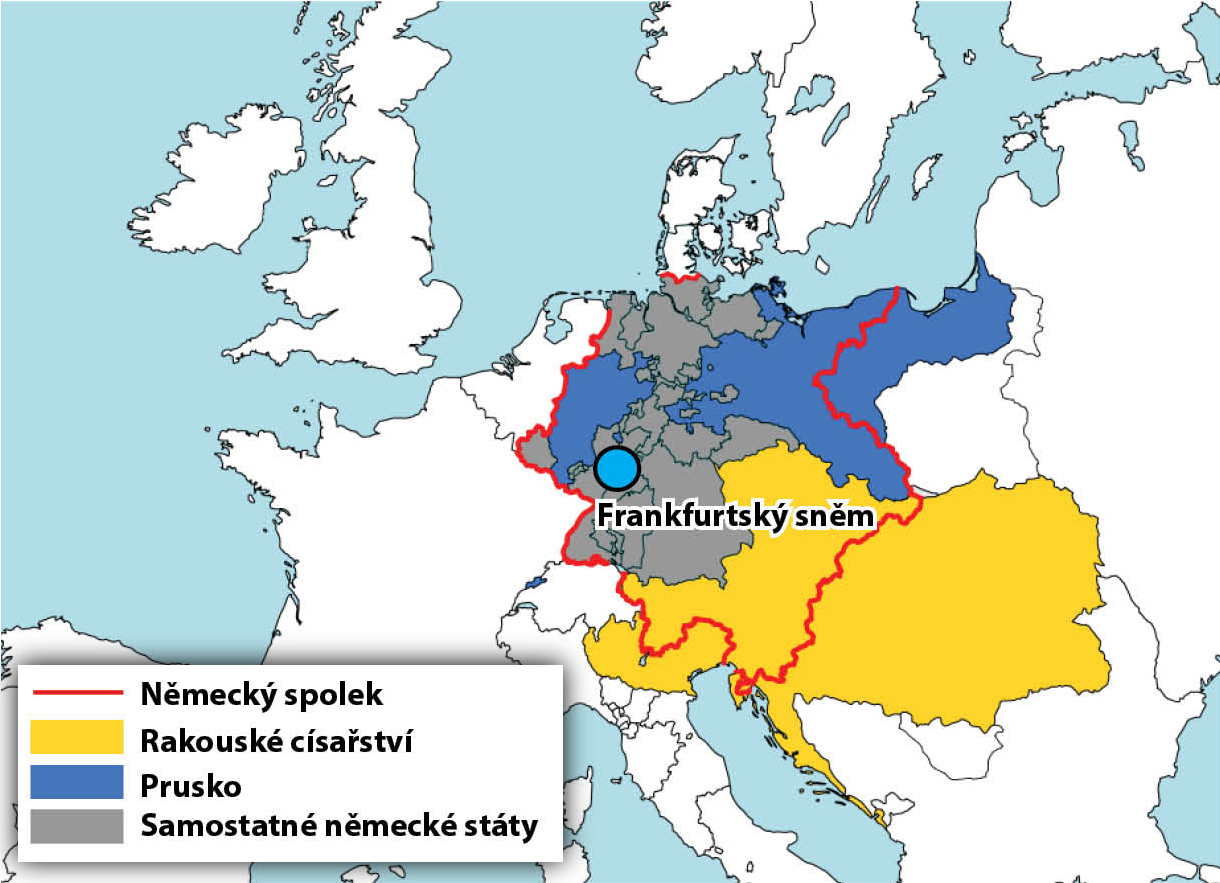

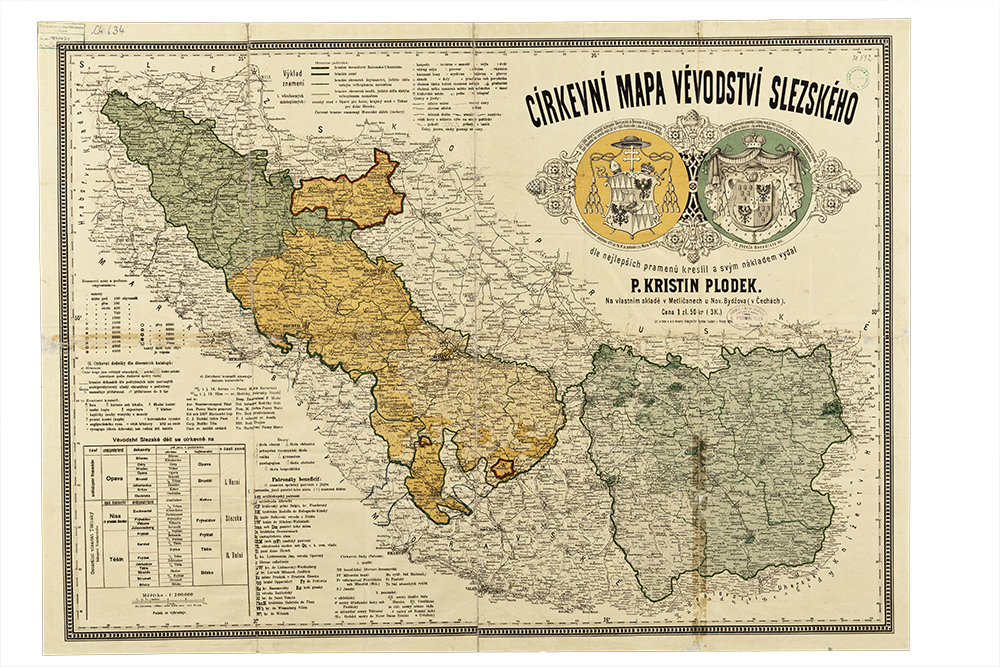

1.3 Development of the state border between 1742-1918

On 11 June 1742, a preliminary (tentative) peace was concluded between Austria and Prussia in Wroclaw under British mediation, ending an eighteen-month military conflict that went down in history as the First Silesian War. The final signing of the peace treaties took place on 28 July 1742 in Berlin. The peace protocol stipulated that the King of Prussia, as the victor, would receive the whole of Lower Silesia and a substantial part of Upper Silesia, including Kladsko, which had never been part of Silesia but Bohemia. Only the whole territory of the Principality of Těšín was to remain part of the Habsburg monarchy, to which was added a part of the lower Estates of Bohumín from the original Ratiboř region, as well as most of the Principalities of Opava and Krnov, a smaller part of the Principality of Nisko-Grotkov and basically all the so-called Moravian enclaves in Silesia. Austria thus accounted for less than 14 % of the total area of Silesia. The name of the newly created territorial unit was adopted as the Duchy of Silesia, later the Duchy of Upper and Lower Silesia, as a reminiscence of the previous state and an expression of state and sovereign prestige. However, it was generally referred to as Austrian Silesia.

The demarcation of the border directly at the places in question began on 22 September 1742 on the border of Těšín and Pštinsk at the confluence of the Bela and Vistula Rivers near the village of Dědice. The boundary in this area was defined by the Vistula Stream as far as the town of Strumen, but further west it continued through open countryside, which led to the need to resolve a number of disputes between landowners on both sides of the boundary line. On the Těšín side, the border consisted of the estates of Zbytkov, Bonkov, Rychuld and Žibřidovice, where the border on the Prussian side began to meet the lower estate of Vladislav. The state border then followed the course of the Petrůvka River to its confluence with the Olše. It followed the course of this river north-westwards until it reached its mouth on the Oder at the village of Kopytov. The only significant exception was the area near Věřňovice, where the commissioners respected the need to preserve the integrity of the estate, which was part of the lower estate of German Lutyně. The border continued upstream of the Odra River to its confluence with the Opava River at Třebovice. As a consequence, the lower estate of Bohumín was divided into two parts, of which the town itself and the villages of Kopytov, Pudlov and Šunychl fell to the Austrians, while the Prussian side included Bohumín Castle with the Old Court and the villages of Zábylkov, Odra, Olza, Velké Hořice and Belšnice.

In the Principality of Opava, the Opava River formed the border to its provincial centre. The territory on the right bank of the river, i.e. Ratibořské Předstí, the village of Kateřinky and the farmlands belonging to the town, remained part of the capital of Austrian Silesia. Not far beyond, to the north-west, the border at the village of Vávrovice reverted back to the course of the Opava, which, against the stream followed the river to the town of Krnov. Just as in the case of Opava, it remained part of its right bank suburbs. The boundary line then continued along the Opavice River, dividing several manors and estates. A similar situation prevailed in the establishment of the borders of the so-called Moravian enclaves, which, however, remained for the most part attached to the Habsburg monarchy.

The situation was rather complicated in the Principality of Nisza, where the commissioners could not take advantage of natural obstacles as in the case of the other territories concerned and were therefore forced to follow the course of local roads, small watercourses and other landscape landmarks, with the primary consideration being the boundaries of the individual landed estates of the nobility. However, this was not always possible. The new boundaries affected the estates of Velké Kunětice and Bílá Voda most visibly. The subsequent disputes that flared up between the owners of the dominions on both sides of the border had to be resolved in a partial way even after the termination of the boundary commission, whose last meeting was held in Bílá Voda on 20 October 1742.

During the demarcation of the boundary, the commissioners and their authorized staff were to set wooden posts in the field where the boundary line would run. In total, 138 of them were planted on the Austrian side. The posts also included signs on which the royal crown was painted, from which a red royal cloak lined with ermine emerged. The mantle bore gold initials: M.T.R.I.H.B.R, an abbreviation of the name and title of the monarch in the Latin version. The translation reads: Maria Theresa, Empress of Rome and Queen of Bohemia. However, the wooden posts could not withstand the weather for long and were therefore replaced by boundary stones. Each of them bore a numerical order marking and in the upper part the emblem of the imperial crown or the Prussian eagle or a combination of both. Their location was recorded on special maps. Only in the area of the boundary of the Principality of Těšín were about 50 of them installed, of which about twenty have survived to this day as a memento of the long-defunct boundary line.

The boundary set in the autumn of 1742 remained in force until the end of the monarchy in 1918.

1.4 Development of the state border from 1918

At the end of the First World War, when the disintegrating Austro-Hungarian monarchy began to form new state units, it was necessary to resolve the course of the state border in the area of the disappearing Austrian Silesia. The territorial demands of the representatives of the Czechs, Germans, Poles and Schlonzaks were based on arguments of historical rights, national and ethnographic conditions and economic interests. A protracted dispute over the territory of the historical lands, which had been constituted and to a certain extent developed as independent principalities since the high Middle Ages, had to be ended only by the intervention of the conciliatory powers.

The Czechoslovak government, however, demanded the annexation of the left bank territory around the Opava River. This was the southern part of the Ratiboř region - the so-called Hlučín region - where approximately 50,000 inhabitants lived on nearly 316 km2. Its annexation to Czechoslovakia was stipulated by the peace treaty signed with Germany at Versailles on 28 June 1919. Despite the obvious disagreement of the majority of the local population, Hlučínsko was merged with the Czechoslovak territory without a plebiscite on 4 February 1920. The work of the de-limitation commission continued until 1923, when the villages of Hata and Píšt were additionally annexed and the village of Ovsiště was returned to Germany.

The situation was most complicated in Těšín. Representatives of a part of the Polish representation established their own group in Těšín on 19 October 1918 under the name of the National Council of the Těšín Region. Poland in its declaration of October 30, 1918, demanding the annexation of the whole of Těšín in its historical borders to the restored Poland. On the same day, the Czechs launched the organisation of the Provincial National Committee for Silesia and on 1 November in Ostrava, Poland, they agreed to take over the government of the entire Silesian territory. The provisional demarcation line, the final form of which was to be decided by the governments of both states, was set on 5 November 1918 according to the national composition of the municipal councils. After the Polish government announced at the end of November 1918 elections to the Constituent Assembly, which, according to the wishes of the National Council, were to be held on 26 January 1919 also on the territory of Těšín, the Czechoslovak government strongly opposed this step and at the end of January 1919 militarily occupied part of Těšín up to the upper reaches of the Vistula. After the intervention of the Agreed Powers and lengthy negotiations, the Council of Ambassadors in Spa on 28 July 1920 decided that Těšín would be divided as follows - Czechoslovakia would receive, according to its minimum requirements, the Ostrava-Karviná district and the Košice-Bohumín railway, i.e. from the historical territory of the principality of about 1,270 km2, where approximately 300,000 inhabitants lived. 1,012 km2 with 140,000 inhabitants were annexed to Poland. The administration of the annexed parts of Těšín was handed over to the Czechoslovak and Polish governments on August 10, 1920. Four years later, the border was additionally adjusted when the settlement of Hrčava was annexed to Czechoslovakia.

The newly demarcated boundaries were set with boundary stones carved with the abbreviation of the states and the year in which they were installed. In addition, a total of 232 border orientation posts made of pressed steel sheet, painted in the form of a stylised national flag and two cast-iron shields with a lion from a small national emblem were erected at border crossings throughout Czechoslovakia in 1925-1926. Forty-five of them were installed at border crossings in the area of Czechoslovak Silesia.

The Polish government also took advantage of the political tensions that culminated in 1938 with the dictate of Hitler’s Germany to cede the Czechoslovak border territory. In several diplomatic notes, it demanded the immediate evacuation of the Czechoslovak part of Těšín, where the Polish minority was most numerous, and the handover of this territory to the Polish state. The seizure included the entire political districts of Český Těšín and Fryštát, and partly affected three villages in the Frýdek district (Šenov, Vojkovice and Žermanice) and later other smaller parts of the Moravská Ostrava district (Hrušov, Heřmanice, Michálkovice, Radvanice and Slezská Ostrava), while, on 10 December 1938, Morávka was incorporated as part of the political district of Frýdek into the second republic, which from 16 March 1939 was part of the historical Silesia in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The area of the territory affected by the Polish occupation was approximately 830 km2.

Western Silesia was granted a protocol signed by Czechoslovakia and Germany. On 20 November 1938 it was annexed to the Reich. The government district of Opava became part of the Sudetenland, while the Hlučín region was included from October 1938 in the Ratiboř district of the Opole government district of the Silesian province (from 1941 Upper Silesia).

The part of Těšín under Polish occupation was occupied by the German army on the first day of the Second World War, i.e. on 1 September 1939, and annexed to the Reich as part of the government district of Katowice.

After the end of the Second World War, Polish territorial claims were not accepted; after the intervention of the Soviet Union, both sides were forced to sign the Allied Treaty on 10 March 1947. A definitive decision on the form of the state border was not made until the signing of the Czechoslovak-Polish Treaty in Warsaw on 13 June 1958, adopted by the National Assembly of the Czechoslovak Republic at its session on 18 September of the same year. A total of 43 changes were made in Silesia, the most significant in the vicinity of Krnov at the confluence of the Opavice and Opava Rivers.

1.5 Development of the internal administrative structure 1742-1918

From 1743, Austrian Silesia was administered by the Royal Office in Opava, which was renamed the Royal Representation and Chamber in 1749 and the Royal Office again in 1763. In 1783-1783, Austrian Silesia was merged with Moravia and administered by a joint Moravian-Silesian Governorate based in Brno. At the same time, it was divided into two regions with seats in Těšín and Opava. After the abolition of serfdom in 1848, the regional authorities ceased to function and Silesia was divided into seven political districts. These were abolished in 1855 and part of their competence was transferred to the mixed district authorities. In 1868 the political districts were re-established. From 1849 the superior authority of these districts was the governorate, which in 1853 became the Silesian regional government.

With the abolition of serfdom in 1848, the dominions were abolished and replaced by state administration offices. At the lowest level, local municipalities were established as local self-government bodies, which were supervised by district governorates administering the so-called political districts. The only Silesian town that acquired a specific status, the Statutory Town of Opava, also had the duties of a district governorate. The judiciary was separated from the political administration, so that each political district was further divided into several judicial districts. Regional authorities were abolished and in Austrian Silesia they were not replaced by any regional governments (political administration bodies) as in Moravia and Bohemia. At the top of the provincial administration stood the governorship, headed by the governor. In Austrian Silesia, in the absence of a regional government, the governor also held the office of regional president and was the direct superior of the district governor. The Moravian-Silesian state was divided and Silesia was once again represented as an independent state represented at the level of state administration by the governorate with its seat in Opava. There was also still an elected a self-governing body - the Silesian Convention (from 1861 called the Silesian Provincial Assembly).

Since the governorship was a state administration body and the regional governments met as self-governing authorities, the governorship was replaced in 1853 by the Silesian regional government in Opava, which combined the competences and tasks of the regional government and the governorship. The Silesian Provincial Government served as the highest administrative authority until the end of the existence of Austrian Silesia. In 1860 it was abolished and Silesia was merged with Moravia, but this change lasted only a year and from 1861 Silesia existed again as an independent country with a provincial government. It was headed by a provincial president.

Seven political districts were established in Austrian Silesia in 1849 - Bruntál, Frývaldov (Jeseník), Krnov, Opava, Frýdek, Těšín and Bílsko. There were 22 judicial districts - Bílsko, Skočov, Strumeň, Jablunkov, Těšín, Fryštát, Bohumín, Frýdek, Bílovec, Klimkovice, Odry, Opava, Vítkov, Albrechtice, Krnov, Osoblaha, Bruntál, Horní Benešov, Cukmantl (Zlaté Hory), Frývaldov (Jeseník), Javorník and Vidnava. When another administrative reform took place in 1855, the political districts were abolished, part of their competences were transferred to the provincial government and part to these judicial districts, which began to be governed by mixed district offices. They were headed by district governors.

In 1868 the judicial and political administration was separated again. The judicial districts remained the same, only in 1869 another judicial district Vrbno (from Bruntál), in 1873 Jindřichov (from Osoblaha) and in 1904 Polish Ostrava (from Bohumín). For political administration, district governorates with district governors at their head were again established. Austrian Silesia was divided into seven political districts, but they were not quite the same districts as before 1855 - Bruntál, Frývaldov (Jeseník), Krnov, Opava, Fryštát, Těšín and Bílsko. Opava as a statutory town had the competence of the district governorates, and the towns of Bílsko and Frýdek subsequently acquired a specific status. This created a three-instance state administration (district governorate - provincial government - state). This administrative system lasted until the end of the monarchy, only in the course of time the need arose to divide the administrative units more rationally, and therefore in 1896 the political district of Bílovec was established, which was split from the district of Opava, and in 1901 the political district of Frýdek, split from the district of Těšín. It consisted of a single judicial district - Frýdek, but in 1904 the judicial district of Polish Ostrava was added to it.

The local government also had three instances. At the lowest level it was represented by municipal boards, at the middle level from 1898 by district road committees and at the provincial level by the Silesian Assembly.

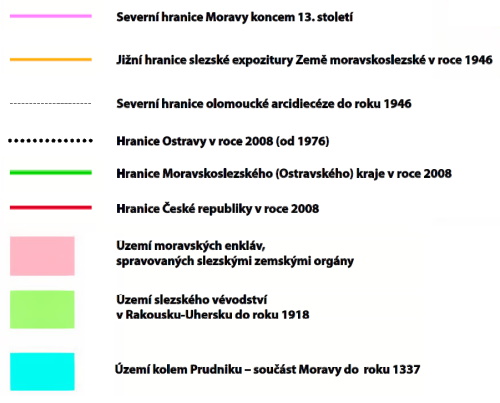

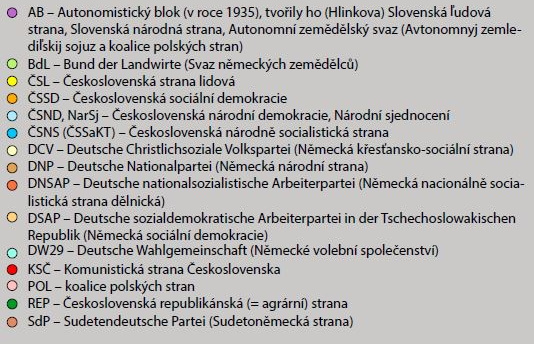

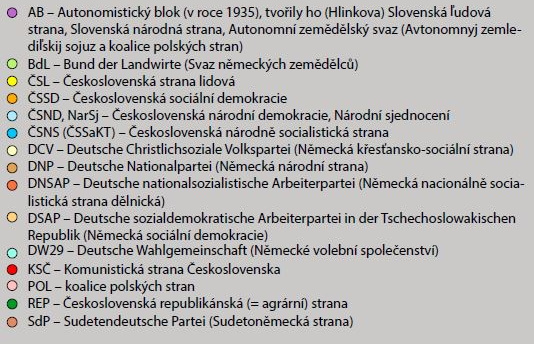

1.6 Development of the internal administrative structure since 1918

After the establishment of Czechoslovakia, the administrative system of Austria-Hungary was adopted. It was not until 1928 that a reform in administration took place, which established the Moravian-Silesian Land. A regional authority with its seat in Brno and district authorities as self-governing bodies were established. During the Second World War, the western part of Silesia was annexed to the Sudetenland and most of the Teschen district to the province of Silesia, later Upper Silesia, with a governmental president in Katowice. Only the district of Frýdek remained in the so-called second republic and later in the Protectorate. After the war, national committees were established at all levels and the 1949 reform created regions. The greater part of Silesia fell under the Ostrava Region and from 1960 the whole of Silesia under the North Moravian Region. The regions were abolished in 1990 but restored in 2000; most of Silesia belongs to the Moravian-Silesian Region, only the Jeseník district belongs to the Olomouc Region.

National committees were also formed at the level of districts and municipalities and for a short time took over state administration. Otherwise, the political districts of Frývaldov (Jeseník), Bruntál, Krnov, Opava, Bílovec, Fryštát and Český Těšín (under the secession of part of Těšín), the statutory towns of Opava and Frýdek, and the district of Hlučín were also newly incorporated into this set-up. The political districts were further divided into the original judicial districts, of which there were 23 in Czechoslovak Silesia.

In 1928, an administrative reform was carried out on the basis of the so-called Organisation Act, according to which the state was divided into four countries - the Czech, Moravian-Silesian, Slovak and Podkarpatorian. Silesia was merged with Moravia and Brno became the seat of the regional authorities. The Silesian provincial government thus ceased to exist. At the provincial, district and municipal levels, administration and self-government were merged. In Brno, a provincial authority was established with competence also for Silesia, headed by a provincial president, who had a council, a committee and commissions at his disposal. The district authorities were divided in the same way, so that the district governor was at the head and had a council, committee and commissions at his disposal. The districts were identical to the previous political districts. At the municipal level, there was a mayor, a municipal council, a municipal board and commissions.

After the Munich Agreement, a large part of Czechoslovak Silesia was annexed to the Reich and became part of the Sudetenland. It fell under the governmental district of Opava, which was divided into 15 rural districts headed by landrats and the city district of Opava headed by a mayor. There were six Silesian districts in total - Bílovec, Bruntál, Frývaldov (Jeseník), Krnov and Opava (urban and rural). The Hlučín region was added directly to the Reich and became part of the Ratiboř district. After the capture of the so-called Zaolzie by the Poles, the districts of Cieszyn and Frysztat were created, which fell under the Silesian Voivodeship with its seat in Katovice. After the occupation of this territory by the German troops, the two districts were merged into one district of Teschen, which was included in the Katowice government district of the province of Silesia, with its seat in Wrocław, headed by the president-in-chief. In 1941, the Silesian province was divided and the province of Upper Silesia was created with the government president in Katowice. Within the so-called second republic, only the truncated district of Frýdek remained, to which several municipalities of the former district of Český Těšín were added. This territory became part of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939. The political district of Frýdek was abolished in 1942 and incorporated into the district of Místek. The territory fell under the Oberlandrat in Moravská Ostrava.

After the Second World War, the administrative division of the pre-1938 period was restored, but the administration was taken over by the National Committees instead of the former authorities on the basis of the Košice government programme. The incorporation of the Frýdek district into the Místek district and the existence of the statutory town of Ostrava (the Moravská Ostrava district was abolished) remained from the period of occupation. In areas with a predominantly German population, district and local administrative commissions were appointed. At the provincial level, Silesia was administered by the Moravian-Silesian Provincial National Committee in Ostrava. However, the Constitution of 9 May 1948 did not speak of provincial national committees, but divided the national committees into local, district and regional committees. On 1 January 1949, regional national committees were established, whose executive bodies were: the council, the chairman (and his deputies), clerks and commissions. The territories of the regions did not respect the provincial boundaries. The Ostrava Region included the Silesian districts of Bílovec, Český Těšín, Fryštát, Hlučín, Krnov, Opava, Ostrava and Vítkov. The districts of Bruntál and Jeseník were incorporated into the Olomouc Region.

In 1960 another administrative reform took place, which maintained the regional system but changed the division of regions and reduced the number of regions and districts. Czechoslovak Silesia, together with the adjacent parts of Moravia, became part of a single North Moravian Region, which was divided into 10 districts, of which Ostrava, Frýdek-Místek, Karviná, Opava, Bruntál and Šumperk districts were in Silesia or interfered with it. These districts continued to exist even after 1990, when the regions were abolished and the main public administration was carried out by district authorities. In 1994, the district of Jeseník was added. In 1997, a law was adopted on the creation of higher territorial self-government units, which were regions with regional offices. The counties were established in 2000, and most of Czech Silesia fell under the Moravian-Silesian Region, with only the Jeseník district under the Olomouc Region. In 2002, as part of the second phase of the territorial administration reform, the district offices were abolished and the territorial units - districts - remained. The competence was partly transferred to regional authorities and partly to municipalities with extended competence.

1.7 Development of buildings in the territory of Czech Silesia

The territory of northern Moravia and Czech Silesia has undergone rapid population changes over the past two hundred years, which have also been reflected in the development of the built-up area. These changes can be observed both in towns and in the countryside. Some settlements have multiplied their population, while elsewhere the population is only a fraction of what it was a century ago. Many villages have become towns, while some towns have become villages due to population decline.

The oldest settlement area is the area of the lowlands, such as the Silesian Lowlands (Opava, Hlučín and Osoblaha part of the region). They are characterised by relatively compact concentrated villages. As a rule, they have houses lined up close together along the road or village square. The interior is significantly separated from the fields by garden fences and roads. The fields, or ploughlands, are divided into blocks - lines, which are further divided into narrow strips - ribbons. Ribbons in different lines may belong to the same building.

The Jeseníky region is a younger area settled mainly in the period of the High and Late Middle Ages (German) colonization. There are planned, usually elongated terraced villages and woodland villages. The houses are arranged loosely along a road or stream, their spacing governed by the width of the strip of fields (ploughland) stretching behind the threshing floor of each farm.

In the area to the east of Ostrava, as in Podbeskydí, the planned nature of terraced villages is less pronounced than in the woodland rope villages; the homesteads are arranged according to the road in irregular boundaries. This transitional type is called a chain village. In the mountainous areas of the Beskydy Mountains, the villages of the youngest settlement have a more loosely grouped mass plan. They are a transitional type between villages and isolated villages.

Mass road villages in the Fryštát (Karviná) and Těšín regions are characterized by irregular construction along the roads. The dispersed Silesian development here is related to the change in the way of subsistence and to population growth, which dates back to the end of the 18th century.

In addition to the above-mentioned types of rural settlements, transitional forms of settlements bearing the features of several types can be found in the territory of northern Moravia and Silesia. It should be emphasised that the character of the settlement changed over time, settlements were created and disappeared, the original character of the settlement was covered by a “new layer.”

Basic types of towns. The towns in the territory of northern Moravia and Silesia can be divided according to type into the following groups: the oldest developmental towns, pre-colonial, with irregular soil (Opava, Krnov), towns founded in a planned manner in the colonization phase of the High Middle Ages, which are characterized by a rectangular plan of their core and a square (Bruntál, Horní Benešov, Hlučín) or the rectangular (Osoblaha, Bílovec, Klimkovice) shape of the square, towns formed from villages, lacking a central marketplace of urban character (Město Albrechtice, Slezská Ostrava, Rychvald), modern towns whose urban function was created in the context of industrialisation (Třinec), and towns planned partly or entirely according to a modern regulatory plan (Český Těšín, Havířov, Nový Bohumín, partly "new" Karviná and "new" Orlová).

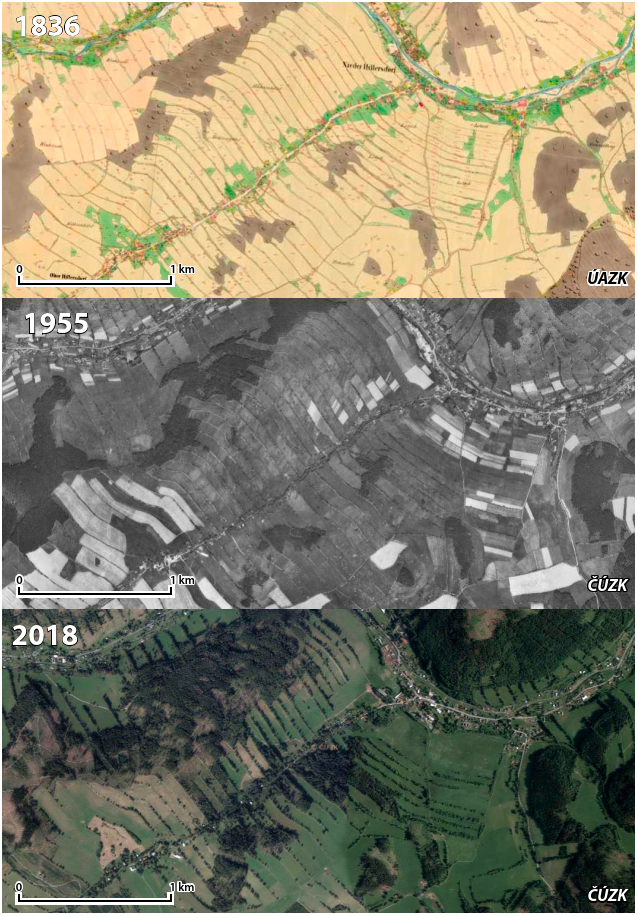

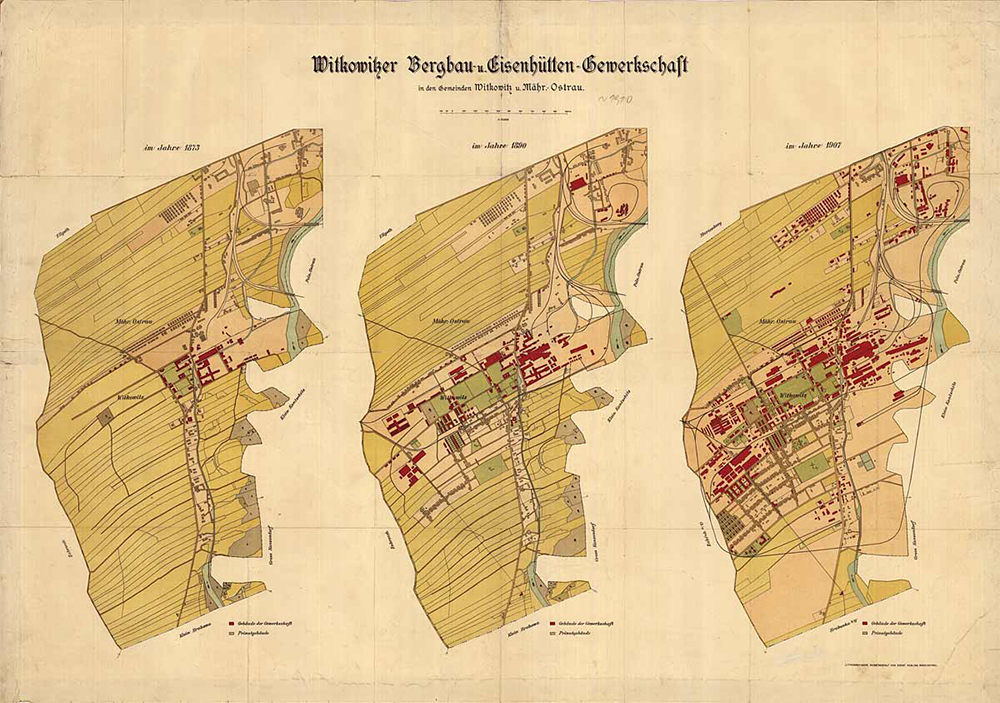

Development of buildings by area. The basis for examining the development of the built-up area are maps of stable cadastre from the years 1830-1840, Prussian military map from 1877, aerial photography from 1955 and regularly scanned colour orthophotomaps from the period after 2000.

Jesenicko. The landscape of Jeseníky is not much affected by the onset of industrialisation, new manufacturing plants are mainly located in the towns. Krnov became the centre of industry and trade for the area in the second half of the 19th century. The laying out of a new road to Osoblaha and the construction of a railway junction in 1872 were of fundamental importance for the town. In addition to the factories, new residential districts developed on all sides of the inner town. Unfortunately, at the end of the Second World War the town was severely damaged. Only the trunk of the historic core remained, the work of destruction completed by socialist expansion. The outer residential districts were less disturbed, but the prefabricated housing did not follow the pre-war street network. Other towns were similarly destroyed at the end of the Second World War, perhaps most notably Osoblaha. The demolition of historic cores and insensitive new construction irreversibly damaged the settlements. In many of them, the central square disappeared and was replaced by a road junction (Andělská Hora), while others lost their town status due to population decline (Osoblaha). With the onset of industrialisation, the rural population is moving to the industrial centres in search of work and its numbers are beginning to decline. At the end of the 19th century, villages with an unfavourable population balance were the majority in Jeseniky. The worst decline occurred in the border districts, with only Krnovsko recording a favourable development. However, the rural population did not change substantially. The turning point came at the end of the Second World War with the displacement of the then predominantly German population. It was not possible to permanently repopulate the area with newcomers from other parts of the country and abroad (Romania, Ukraine); houses fell into disrepair, some villages disappeared, others persisted with a much lower population. Abandoned cottages are being used for recreational purposes, and the construction of cottages and company recreational facilities is being encouraged. Intensive agriculture is replaced by pastoral livestock farming in places with less favourable conditions, and sloping fields are overgrown with trees. Despite this, smaller and more remote settlements retain their original visual character, the division of fields is still clear, and valley villages remain as they are (Holčovice, Heřmanovice). In contrast, villages with good transport access to commuting centres are expanding into the landscape with flat houses.

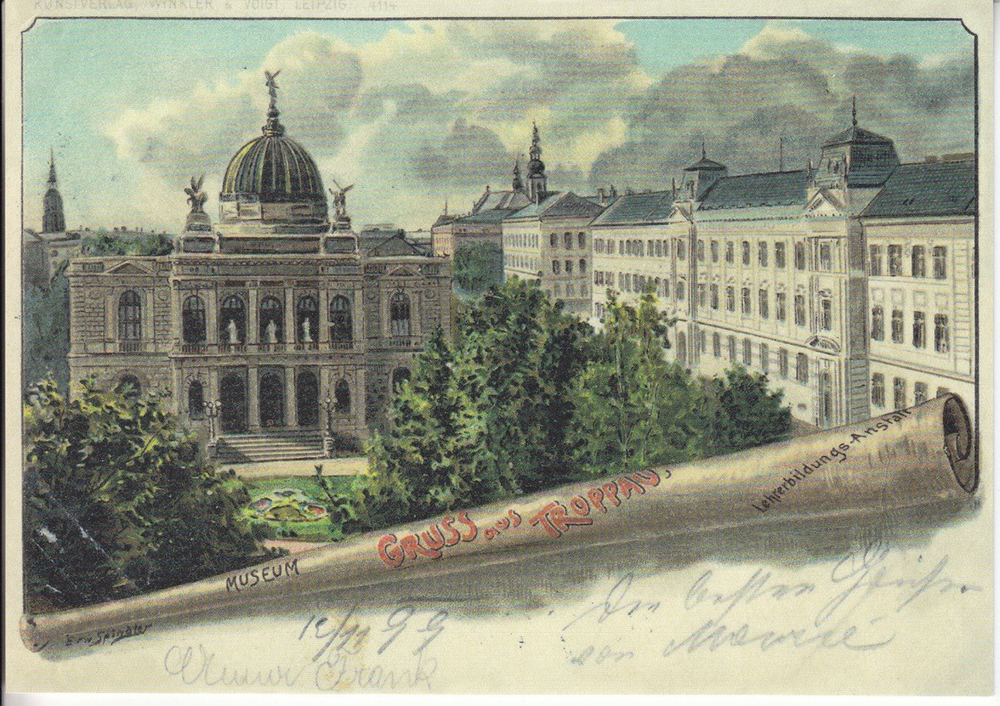

Opava. The agricultural region of the Silesian Lowlands was increasingly influenced by Opava as an important regional centre. Although at the time of the onset of industrialisation Opava was economically behind Krnov, it was the administrative centre of Austrian Silesia and a town consisting of schools. Its urban development reached its peak around the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, when, among other things, representative districts of tenement houses were created. In the 1920s, the development of the town continued with the construction of residential districts. However, the Opava region suffered greatly in the fighting of the so-called Ostrava Operation at the end of the Second World War and the town of Opava was 70% destroyed. Fortunately, the radical plan, which envisaged the redevelopment of the rest of the historic core, was not implemented, but many houses, especially Art Nouveau ones, were demolished in the following years. The post-war urbanisation did not respect the historical context, and in the 1970s and 1980s mainly prefabricated housing estates were built. The suburbs or the formerly independent village of Kateřinky were also overlaid with new buildings. The Opava region had also been marked by stagnation and population decline since the end of the 19th century, although to a lesser extent than Jesenicko. The villages, however, still retained their agrarian character in the 1950s and the distinctive features of concentrated villages with fields divided into thin strips. In the second half of the 20th century, due to the collectivisation of agriculture, the character of the landscape changed from a series of narrow fields to large meadows. The formerly neat, compact villages near Opava began to grow into the landscape (Otice, Slavkov, Kylešovice). Suburbanisation trends have intensified since 2000, but the more distant villages still retain their original character (Brumovice, Loděnice, Tábor).

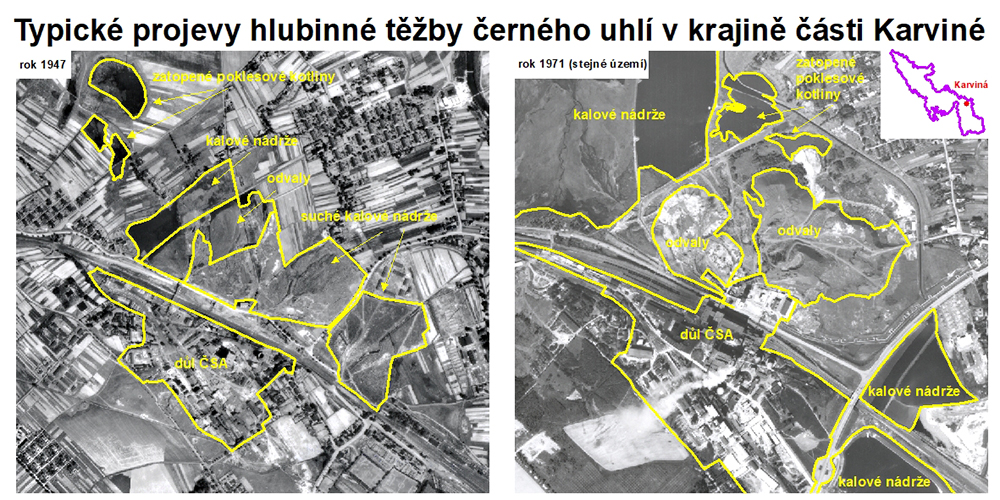

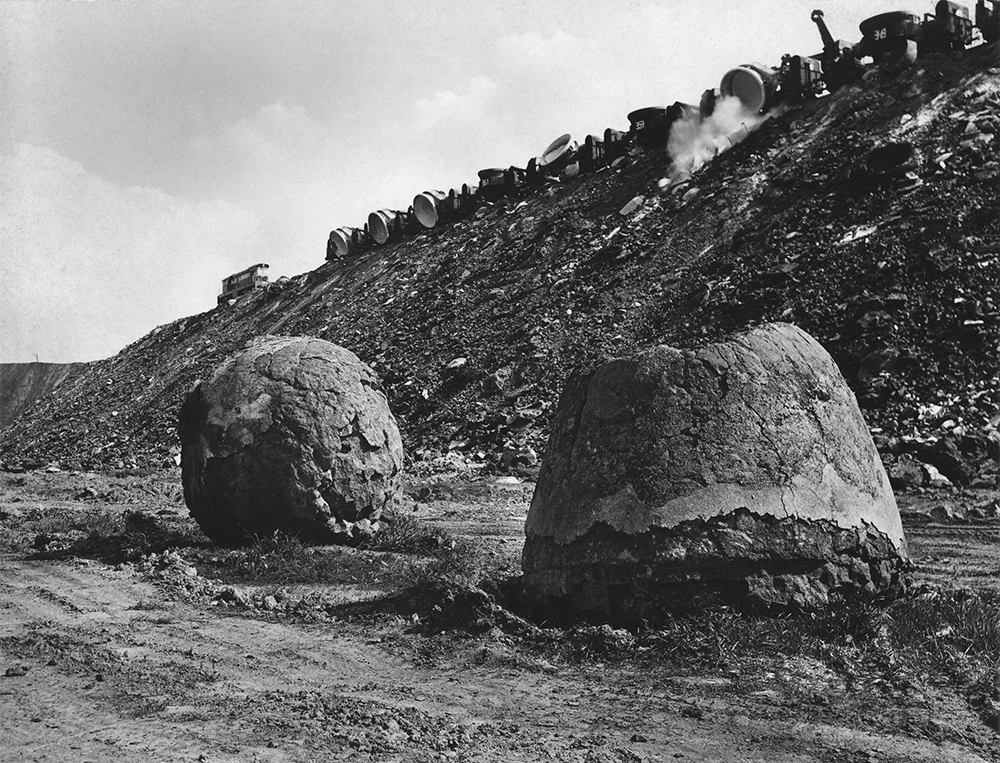

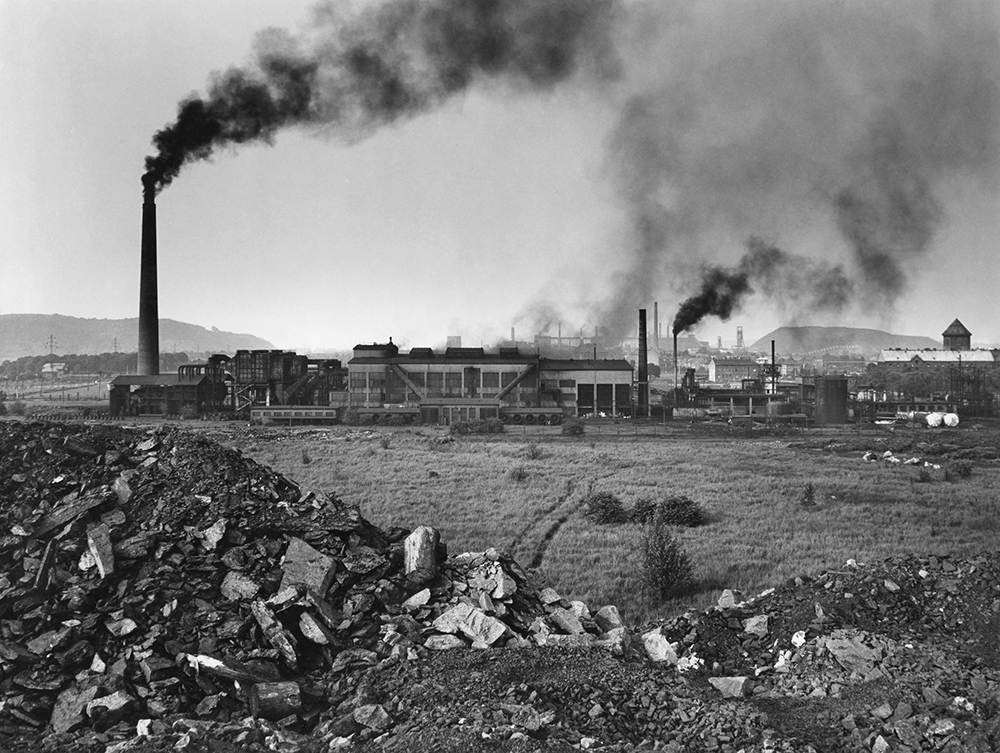

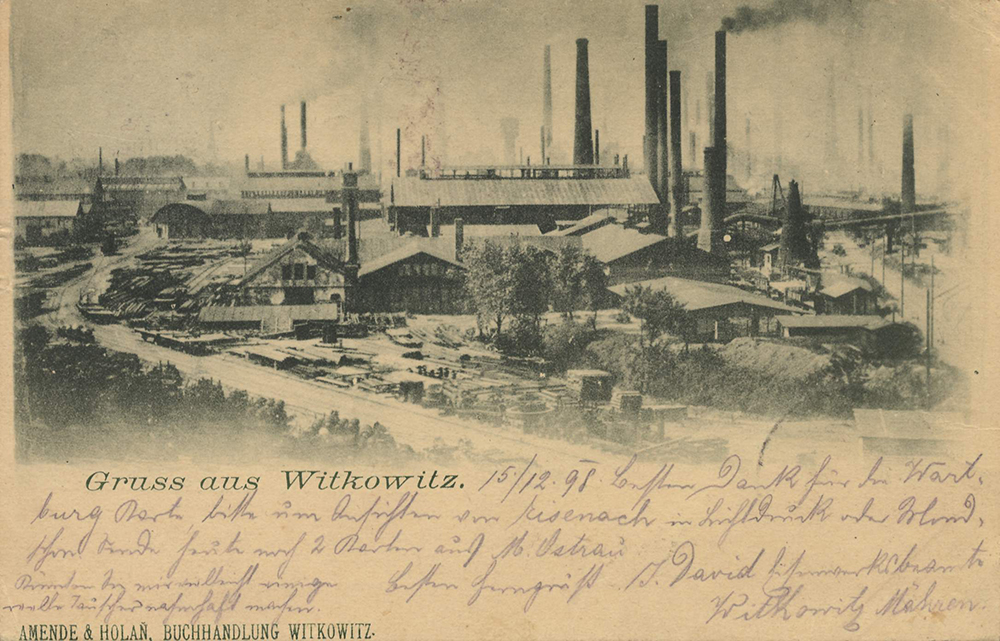

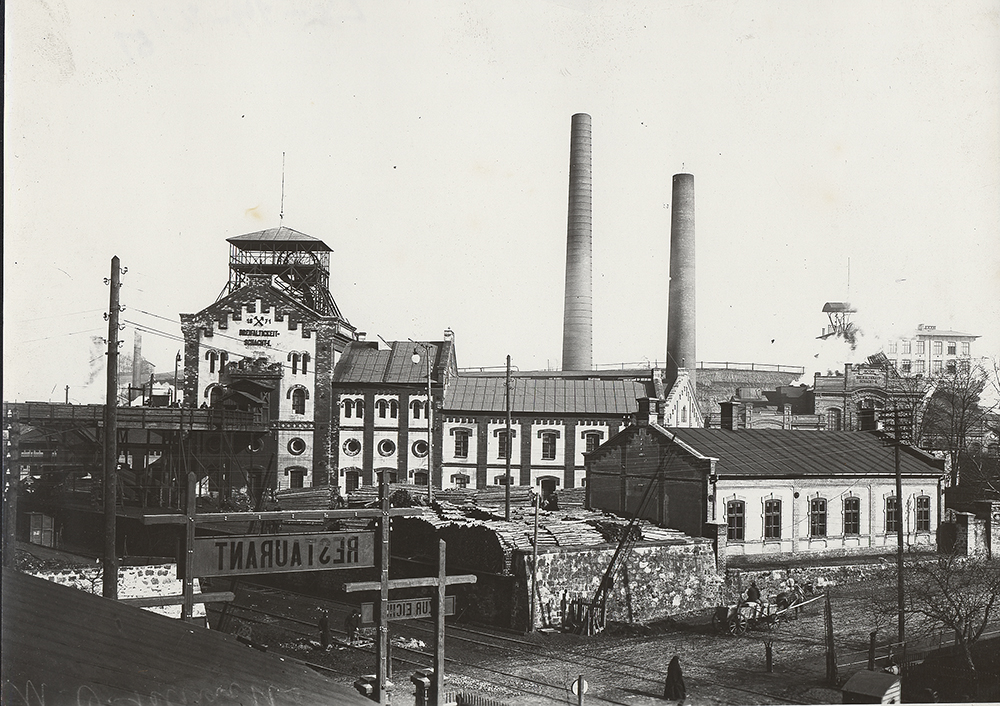

Fryštát (Karviná) and Těšín. The eastern part of Czech Silesia has undergone the most rapid development since the beginning of industrialisation, mainly connected with coal mining and heavy industry. In the Ostrava, Bohumín and Fryštát regions, two-thirds of the villages have experienced explosive growth thanks, among other things, to immigration from Halych. In addition to the towns, villages within reach of employment opportunities are gaining in population. Irregular chain villages and scattered housing developments are beginning to thicken. The possibility of enjoying oneself other than by working in the fields has upset the agricultural tradition and social structure. A division of fields, unthinkable until then, occurred, as the yield from the harvest was only a supplement to the family income. The distribution of homesteads was mostly spontaneous and linked to local roads. Nevertheless, shortly after the Second World War it is still possible to observe considerable differences in the density of housing in the more rural parts of the area, especially near mines where mining colonies have proliferated (Rychvald, Petřvald, Orlová-Poruba) and in more remote locations where the housing is still relatively sparse (Střítež, Návsí, Vendryně). Since the second half of the 20th century, residential development has been thickening even outside the industrial centres and in most of the area it is losing its original character of a dispersed settlement and large distances between individual farmsteads and gradually covers almost the entire cadastre.

The landscape of Karviná has changed the most. As a result of mining activities and their consequences, parts of settlements (Orlová) or entire settlements (the original Karviná) have disappeared. The new Karviná began to be built as the first of the new settlements of Ostrava as early as 1947, when the satellite town of Stalingrad, later called Nové Město, with an axial boulevard of Osvobození Avenue, was founded north of Fryštát. As a result, the population grew from about 8,500 to about 27,800 between 1950 and 1961. As part of the controlled development of the fuel base, the first embryonic settlements of so-called two-storey houses began to be built within an accessible distance from the mines. In 1955 it was decided that the housing estates in Šumbark and Dolní Bludovice would be merged to form a new town, for which the name Havířov was chosen. The axis of its urban composition became the boulevard Hlavní třída, formerly the Těšín road.

According to a premeditated urban plan, much earlier, in the 1920s and 1930s, Český Těšín was built after Těšín was divided by the state border and its historical centre remained on the Polish side. The town centre was built. The Main Street and the main rectangular square with the town hall (1929) became the basis of the composition of the town, situated between the railway and the Olše River. The central part of the town was bounded to the south by today's Střelniční Street, but more loose suburban development continued further south between the railway and the river and also west of the railway. This part of the town is characterised by the trident of the Ostravská, Frýdecká and Jablunkovská roads, later supplemented by the road to Fryštát. An example of a village that became a town in 1930 is Třinec. The importance of the settlement grew thanks to the establishment of a metallurgical and ironworks complex in the late 1840s, which later became Třinec Ironworks.

2. SPATIAL-GEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXT

CONTENTS OF THE CHAPTER

2.1 Geology

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.2 Geomorphology

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.3 Waters

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.4 Climate

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.5 Vegetation

Mgr. Lukáš Číhal, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.6 Vegetation - non-native and invasive plants

Mgr. Lukáš Číhal, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.7 Companion (synanthropic) animals

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.8 Invasive animal species

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.9 Endangered and rare animals

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.10 Immigrants

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.11 Curiosities and rarities

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.12 Returnees and disappeared

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.2 Geomorphology

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.3 Waters

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.4 Climate

Mgr. Lenka Jarošová, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.5 Vegetation

Mgr. Lukáš Číhal, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.6 Vegetation - non-native and invasive plants

Mgr. Lukáš Číhal, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.7 Companion (synanthropic) animals

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.8 Invasive animal species

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.9 Endangered and rare animals

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.10 Immigrants

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.11 Curiosities and rarities

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.12 Returnees and disappeared

Mgr. Martin Gajdošík, Ph.D. (SZM)

2.1 Geology

Silesia is characterised by an extraordinary diversity of geological structure, as two large geological units - the Bohemian Massif and the West Carpathian Mountains - intersect here. This is linked to geological and mineralogical conditions. The Hercynian, or Variscan, mountain-building march, which took place approximately 380 to 300 million years ago, from the Upper Devonian to the Lower Permian, was of fundamental importance for the geological development of the Bohemian Massif. The best preserved remnant of the Variscan mountain range is the Bohemian Massif. The Variscan mountain-forming processes formed it into a solid unit that was not later folded and was gradually overlain by Mesozoic and Tertiary sediments. It acquired its present form in the Quaternary period, mainly due to glaciation and the subsequent formation of the river network.

Proterozoic (ancient mountains). To this oldest geological period belong the varisci of strongly reworked rocks in the cores of vault structures or trusses in the metamorphic Silesian in the Rough Jeseník (Desen and Keprinic vault). Paleozoic (protohistoric). In the Moravian-Silesian region, Devonian mountains are widespread, which are exposed in numerous surface outcrops in the Rough and Low Jeseník. Interesting Devonian fauna comes from Chabičov and Horní Benešov.

In the Lower Carboniferous, marine sediments (Kulm facies) are completely predominant, while in the Upper Carboniferous, freshwater sediments predominate, which reflects climatic changes and the effects of mountain-forming movements of the Variscan folding. The Lower Carboniferous deposits are at their greatest extent in the Low Jeseník, where they are developed mainly in the shale and gravel or Kulm Formation. The sea was present in our area in the Lower Carboniferous about 340 million years ago. Marine fauna is relatively species-poor and has a similar composition in many localities (Zálužné, Nové Těchanovice, Lhotka). In the Upper Carboniferous, about 320 million years ago, the area of Moravia and Silesia became arid. A vast plateau was formed, which we now call the Upper Silesian Basin. At that time, the area was close to or right on the equator, the climate was humid and warm and the plateau was overgrown with vegetation. The Carboniferous forest was created, one of the most remarkable terrestrial eco-systems in the history of the Earth. Thanks to the warm and humid climate, the mass of Carboniferous plants gave rise to black charcoal with a wealth of plant and animal fossils.

Mesozoic. A remarkable period of the Mesozoic was the Upper Jurassic, 150 million years ago an organogenic reef developed in a shallow tropical sea, formed by massive, coiled shells of bivalves and corals (Kotouč near Štramberk).

Three Thorns. The sea, which last swept through Moravia and Silesia in the younger Tertiary, left fossils of various molluscs, but mainly complete fish skeletons, in the layers of clay sediments of the Opava Bay after its retreat 14-13 million years ago. The precipitation of mineral salts from the supersaturated sea water created gypsum deposits (Opava-Kateřinky, Kobeřice).

In the central part of the Low Jeseník lies a group of volcanoes that were active at the boundary between the Tertiary and Quaternary periods. The formation of the volcanic bodies during the Tertiary and Quaternary is related to the intense mountain-building activity of the Alpine folding in southern and eastern Europe. The volcanoes have the character of stratovolcanoes, i.e. mixed volcanoes (Velký Roudný, Uhlířský vrch, Mezina).

The quaternary began approximately 1.8 million years ago and is still ongoing. In the older Quaternary (Pleistocene), periods of warm climate cycled with periods of global cooling. During the glacial periods (glaciations), continental and mountain glaciers expanded and melted again during the warmer periods (interglacials). In Silesia and northern Moravia, continental glaciers encroached on the territory during two Ice Ages, which are classified as the Middle Pleistocene.

In Silesia there are minerals of igneous rocks and accompanying minerals formed from hot solutions (hydrothermal minerals), minerals of transformed (metamorphosed) rocks, minerals in sedimentary rocks and recent minerals, i.e. minerals formed in the present. The Opava meteoric irons are considered unique in the world; their uniqueness lies in the fact that they were found in 1925 in the context of a Palaeolithic settlement 18,000 years old. The discovery of several fragments of a stone meteorite in the village of Morávka in 2000 is also unique.

2.2 Geomorphology

The landscape of Silesia and the adjacent parts of northern Moravia is extremely varied, with different types of georelief, ranging from plains and lowland hills to the highlands of the Hrubý Jeseník Mountains and the Moravian-Silesian Beskydy Mountains. Three geomorphological provinces meet here: the Bohemian Highlands in the north-west and the Western Carpathians in the south-east, with a relatively small spur of the Central European Lowlands intervening in the north.